By Eli Solomon

Singapore celebrated its 150th year of modern existence in 1969. Only a year earlier, motor sport embraced the “black art” of aerodynamics in the pursuit of greater speed. Sugar, Sugar; Hooked On A Feeling; Honky Tonk Women; and Get Back were songs that were played on our Radiogram at home. Apollo 11’s moon landing had captivated my attention and Bee Gees was the favourite band of this youngster. Closer to home, that 45 minute drive from Katong to Sembawang Hills with my dad in his Simca on Good Friday effectively set me down the slippery slope of motor sports damnation.

A poster from the 1969 Singapore Grand Prix hangs off a wall in this writer’s garage.

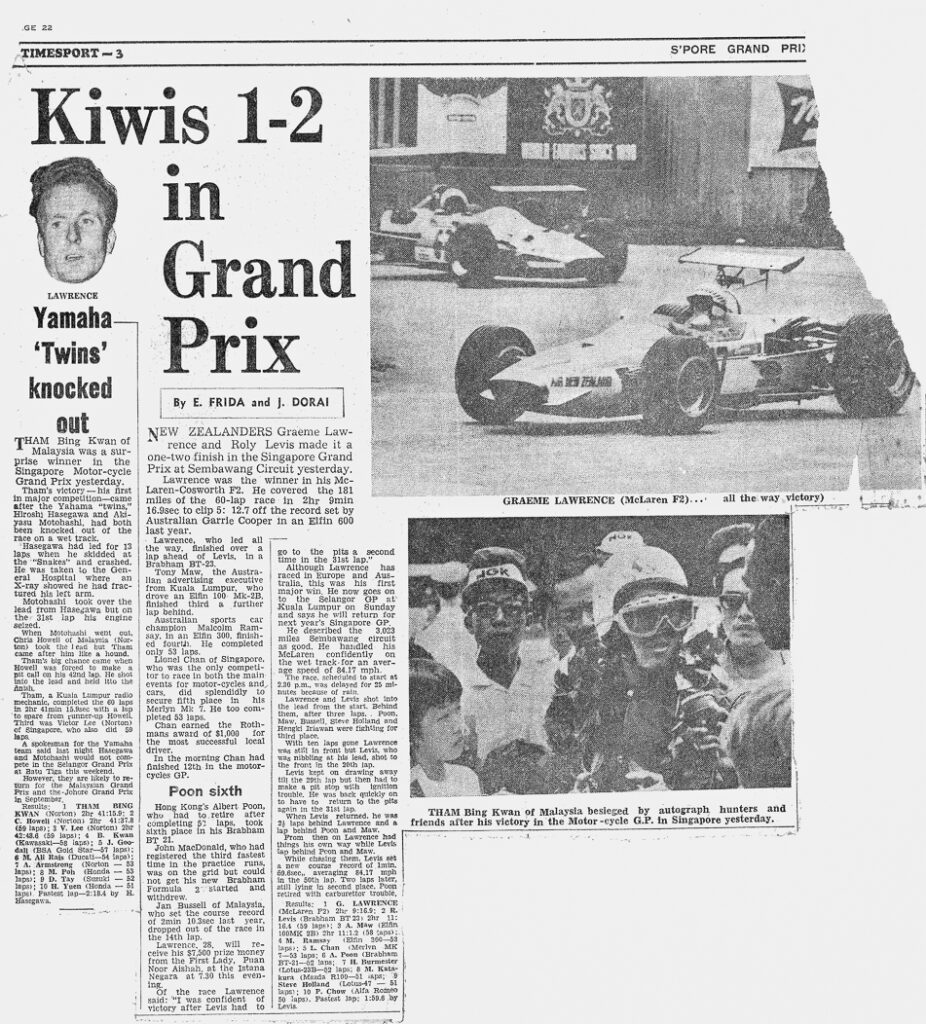

The Singapore Grand Prix, now in its ninth year would, for the first time ever, see racing cars arrive with aero aids fitted. 1969 was also the year Australia and New Zealand woke up to the local Grand Prix for it was only a year earlier that Aussie Garrie Cooper had set things alight by winning in Singapore in his Elfin 600 prototype. It was a car with no wings and running on cross-ply threaded tyres. A revolution was at hand.

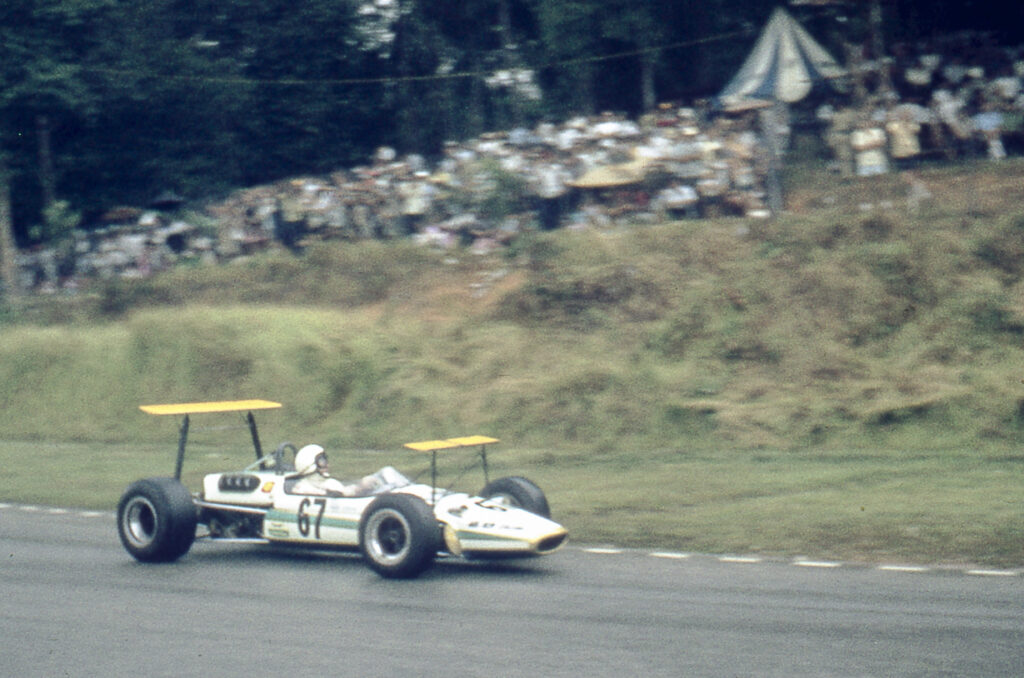

The foreign competitors were treated to customary Asian hospitality when they arrived. When Kiwi Graeme Lawrence’s McLaren M4A (M4A-14) was unbundled at Paya Lebar Airport, it was to an astonished crowd. The McLaren had aerofoils that most had only read about in Autosport, Motorsport and Racing Car News. While the McLaren’s appeared somewhat modest, fellow Kiwi Roly Levis’ Brabham BT23C (BT23C-7) was anything but. The Brabham appeared to have sprouted wings that were high enough to transmit TV signals back to Auckland!

Off to scrutineering for the 1969 Singapore Grand Prix, sans rear wings. The downforce canards on the front were extremely modest.

The Levis and Lawrence cars side by side in the paddock in Singapore in 1969.

We were going to be entertained by Formula 2 cars with inverted wings 66 years after the Wright brothers used such devices to get a petrol-engine aircraft off the ground. Roly would be using his wings turned to do the opposite. On top of this entirely new experience, both Singapore and the Batu Tiga races offered anyone with a car to battle it out in a race against such revolutionary prototypes, mixing Mini Coopers, Mazda R100s, a Porsche 911S, a Lotus 23B, a Jaguar E-Type and even a 1600cc Alfa Romeo GTV against the likes of McLaren, Brabham, and Lotus. And all of this around a street circuit that once had the world’s best grafted-rambutan plantation!

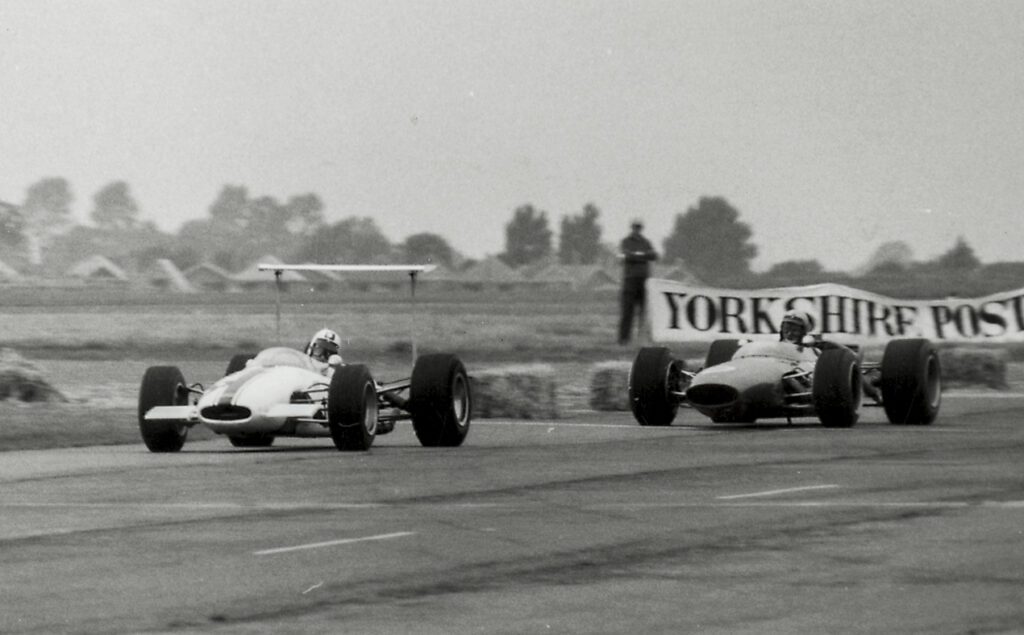

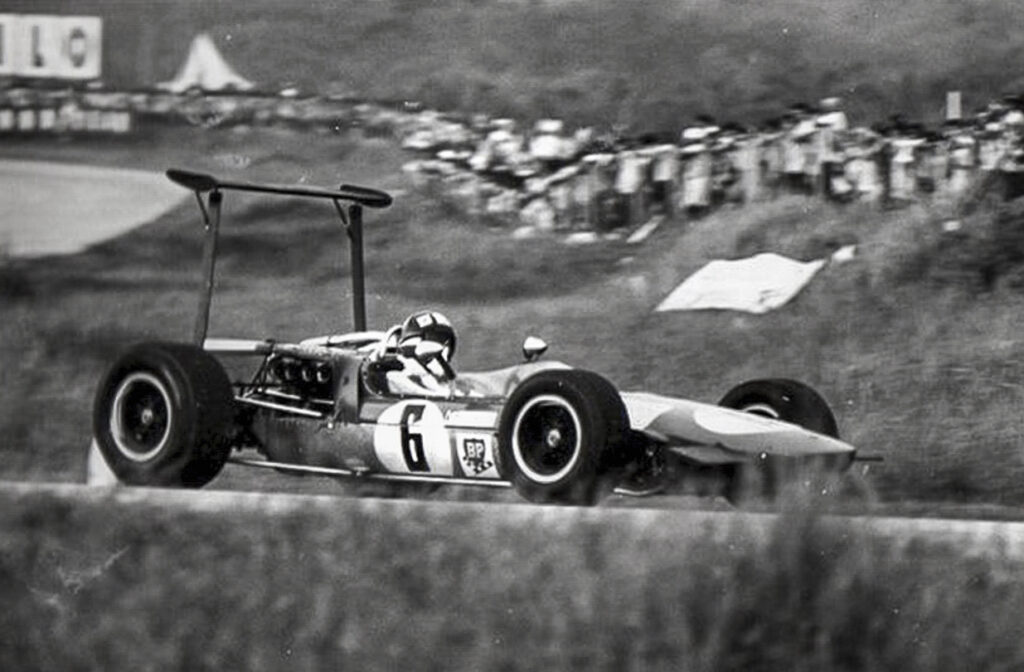

Roly Levis’s Brabham BT23C-FVA might have been a Formula 2 car from 1967 but it had been developed to the point where it was a frontrunner in its class in 1969, complete with FVA motor and bi-wings. Spectators watching the BT23 around Old Upper Thomson Road and at Batu Tiga must have been wondering if the wings were about to fall as they tilted to the movements of the wheels.

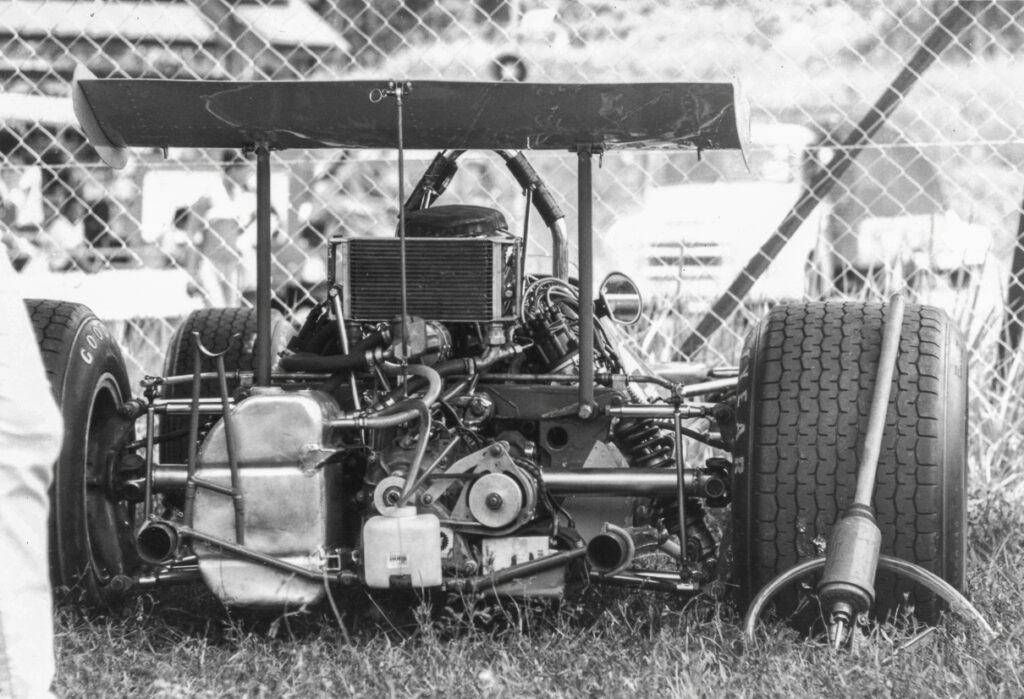

Compare the Brabham BT23C’s rear wing set up with that of the McLaren M4A’s pictured above. The McLaren’s wing struts were not mounted to the rear wheel carriers as was done on the BT23.

Graeme Lawrence’s McLaren M4A was constructed while Graeme was working for Bruce McLaren at the McLaren factory in Colnbrook, Slough in the Berkshire. Over lunch in Auckland one year, he told me that he “…looked upon Bruce McLaren as a god…But it [the M4A] wasn’t right.” After a test session at the Crystal Palace Circuit in London in 1967, well-known Australian race driver Frank Gardner told Bruce that he couldn’t understand how he could “drive this piece of shit!” McLaren’s Formula 1 and Can-Am cars were now taking up a lot of his time and this impinged on the development that could be dedicated to the lower formulae racing cars designed by Robin Herd.

Graeme soon took the right steps to develop the car. “We lowered the suspension arms…we altered the roll bar linkage and we also cut a hole in the bottom of the tub so we could get the engine sump off to work on the bearings. We took the car home to New Zealand and every meeting we were 1 to 2 seconds faster than Piers Courage in a factory-prepared McLaren M4A. “There had been a total lack of development of the M4 and following the Lotus mantra of the time, the driver would also play the role of development engineer. The Kiwi, who would race four different single-seaters in Singapore and Selangor from 1969 to 1973, recalled that this McLaren of 1969 was the most difficult of his cars to drive, “…like trying to dance with an octopus on a tight wire.” It would also be his first visit to Singapore, and the fist of this Treble-Doubles, winning the Singapore and Selangor Grand Prix back to back between 1969 and 1971, a feat no one was every able to match.

Levis chases Lawrence on the Upper Thomson Road circuit during the 1969 Singapore Grand Prix. Both cars had similar Cosworth motors – 1.6-litre four-valves per cylinder FVAs.

“We were still some ways from seeing sponsorship money thrown into Asian motor racing, the entire Grand Prix sponsorship and donations for 1969 amounted to a paltry S$64,500, of which Rothmans accounted for $25,000. At the other extreme, Tay Koh Yat Bus Company, soon to be put out of existence, donated $500. The writing was on the wall as the local and international media lapped up this unusual street event that now featured some top class names and cars.

An advert showing both the McLaren M4A as well as the Brabham BT23C. Notice how different the rear wings were setup on either car. The Brabham’s wings had struts mounted on the wheel hubs, which was

Graeme Lawrence’s McLaren was a state-of-the-art semi-monocoque, a bathtub that made the spaceframe technology of the 1960s obsolete. Roly Levis’s BT23C was a much more conventional spaceframe contraption, a 1967 Formula 2 car that itself was had significant alterations from the earlier line of BT10-BT18 Brabhams. But the ex-Frank Williams BT23C was still a far more successful car than the McLaren M4A in its class. The other top contender was Garrie Cooper in a BOAC-backed Elfin 600C, a car that captured the imagination of a naïve media that bought the story that this was a Formula 1 car, hook, line and Repco V8 sinker. Sadly, a engine issue prevented Cooper and the Elfin 600C from starting in Singapore. As an aside, Cooper and his very first Elfin 600 Prototype had also captured the imagination of the local public a year earlier by winning the 1968 Singapore Grand Prix and putting an end to local and Hong Kong domination. Still, the new 1969 Elfin had yet to embrace aerodynamics and remained a fairly minimalist racing car.

Prior to John Macdonald acquiring the Brabham BT10 in early 1969, Chris Meek had already racing it in Formula 2 events in Europe in 1968 with a high rear wing.

There were other notable cars on the grid for the Singapore Grand Prix, including a Brabham BT10 with enormous history in the hands of Cosworth’s Mike Costin. This car was referred to by some as Costin’s Mule [See COSTIN’S MULE]. John Macdonald had continued to develop the car with some serious modifications over the coming years. The car had already raced in Europe with rear wings in the hands of Chris Meet but MacD was loath to use them around the tight Singapore circuit. When he did, it was only for qualifying in 1970. During that Grand Prix, the front wings were removed. Even then, the fronts were attached by a broomstick! Macdonald realized that those wings did not work so well for the car on a winding circuit and recalled that “wings may not have done anything except increase the confidence of the man at the wheel.”

John Macdonald’s Brabham BT10 with its rear wing attached in the Singapore paddock ahead of the 1970 Singapore Grand Prix.

The organisers in Singapore and Malaysia were intent on attracting the best talents in the region and spared no expense in getting them over. Particular attention was spent on the Australians and Kiwis, which was not difficult as these drivers were keen to do a series that did not just cover South East Asia (Singapore and Shah Alam) but Penang, Macau and Japan as well. The great Aussie invasion would not materialize till 1971 however. In 1969, the Singapore Grand Prix, held over the Good Friday weekend, coincided with the second round of the Australian Gold Star Championships at Bathurst’s Mount Panorama circuit. Even without the like of Kevin “Big Rev” Bartlett, there were some well-known names such as Brian Foley, Garrie Cooper and Malcolm Ramsay, alongside the Kiwi pair of Lawrence and Levis.

We all know that wings were banned in international racing after the 1969 Monaco Grand Prix and wing height reduced automatically once designers figured out that downforce could be enhanced with bodywork extensions, without the need for scaffolding. But that was well after the Easter Grand Prix weekend. Lawrence and Levis had the edge in Singapore and Selangor and Lawrence romped home to back-to-back Grand Prix wins with Levis setting FTD at both circuits. As a matter of interest, the previous lap record around the Singapore street circuit was 2:10.264, set by Jan Bussell in his Brabham. Roly Levis’s fastest lap in Singapore in 1969 was 1:59.6! This was done on the 50th lap as he tried to make up time following ignition trouble at half distance (he was leading the race at the time). He repeated that feat the following weekend, setting a new lap record of 1:24.2 around the Batu Tiga Circuit.

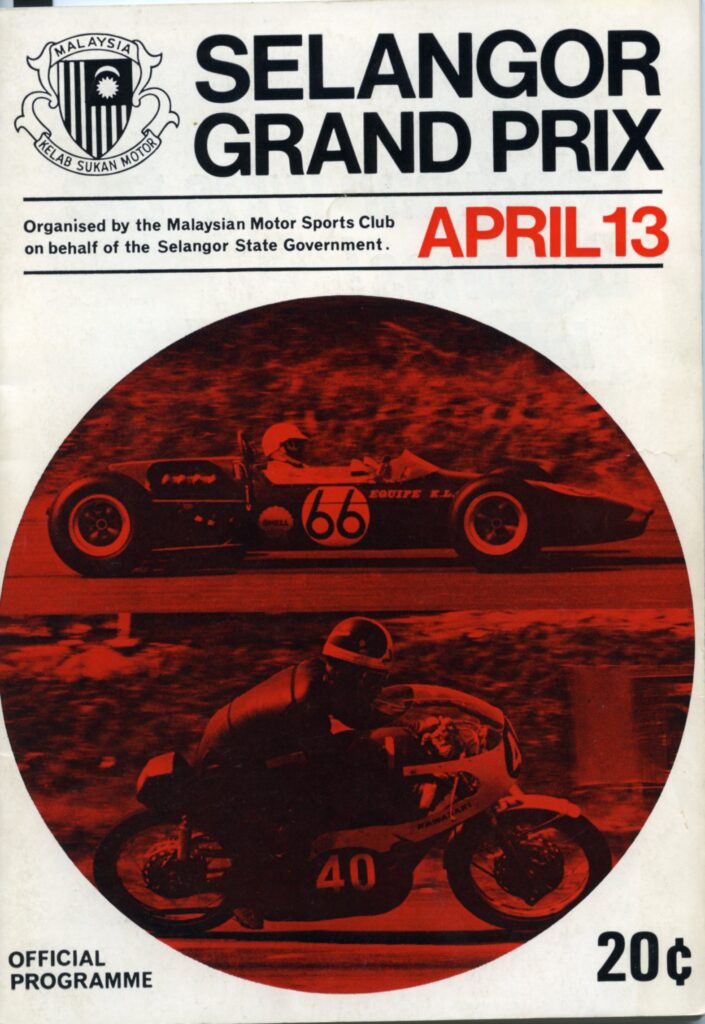

Program cover from the 1969 Selangor Grand Prix.

Front row of the 1969 Selangor Grand Prix grid with Roly Levis and the Brabham BT23C on pole to the left, Graeme Lawrence and the McLaren M4A in the middle and Garrie Cooper and the Elfin 600C Repco V8 to the right, following surgery on the motor by his chief engineer Bob Mill and team-mate Malcolm Ramsay. A second Elfin, a Mk1 Mono entered by Tony Maw and sponsored by BP-BOAC, also carried a radical rear wing. A total of five cars raced with aero aids that weekend in Selangor.

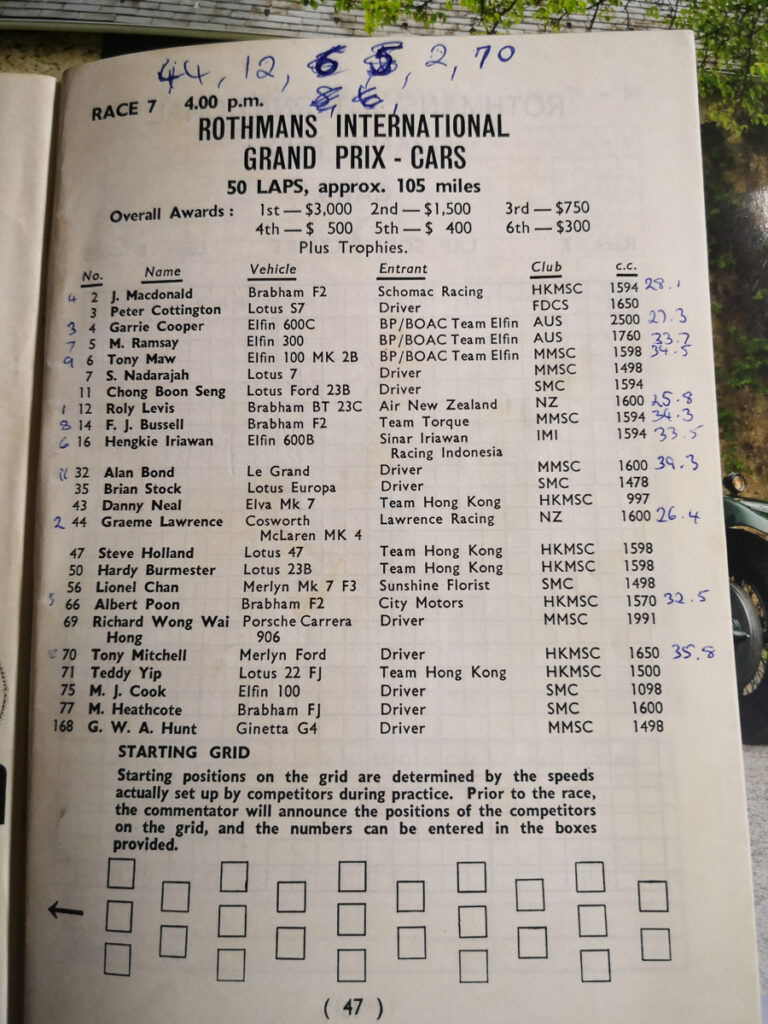

Entry list for the 1969 Selangor Grand Prix with finishing order.

Tony Maw and his BOAC-Team Elfin 100 Mk1 Mono, kitted out with the high wing for the Selangor Grand Prix the weekend after Singapore. The Elfin had finished third in Singapore and would repeat the feat at Batu Tiga the following weekend.

Malaysia’s post-independence history treats 1969 “as a watershed that marks the beginning of a new era in the country’s political, economic and social development.” One can almost say that same for motor sports on both sides of the Causeway. Wings were soon followed by slicks and soon the big backers showed up – Cathay Pacific, Malaysia-Singapore Airlines (and later on SIA), Air New Zealand and the king of all contributors to the world of sports, Rothmans. Motor racing in Asia was about to come of age.

APPENDIX 1 – WINGS

From the fertile brain of Colin Chapman came the rear wing in Formula 1 at Monaco in 1968 – but that wasn’t the first time wings were adapted to a racing car (see APPENDIX 3). Chapman’s wing was a modest affair but it must have struck a cord with Ferrari’s Mauro Forgheri because two weeks later at Spa-Francorchamps, Chris Amon’s Ferrari 312 had an inverted wing supported by two posts linked to wheel hubs. All hell broke loose after that and before long, they were on just about every Formula 1 car on the grid. Following accidents in Monaco the following year (May 1969), wings were banned and the rules rewritten. Aero aids were reintroduced but with restrictions – the Formula 1 and aero experts have written extensively about this. But back in Singapore and Selangor in 1969, there were no rules as such.

A Lotus 49 prior to the introduction of aerodynamic wings. This car was participating in the 2010 Tasman Revival at Eastern Creek in Sydney. Notice the provision for front wings. Rewind Media Collection.

Rear wing on a car in the Singapore Grand Prix paddock in 1970 showing the struts bolted to the rear uprights instead of the rear wheel hubs.

McLaren’s M7C, known as the Thursday Car because it was banned on the Thursday before the 1969 Monaco Grand Prix. The huge downforce created by the rear wing necessitated a third set of wings – a guillotine mounted on the front suspension arms. Rewind Media Collection.

APPENDIX 2 – CHAPARRAL’S WINGS

The 1966 Chaparral 2E with its rear wings. Rewind Media Collection.

Chaparral 2F’s wing was mounted directly to the rear hubs with the struts located by longitudinal radius rods and a transverse Watts linkage that was pivoted on a vertical aluminium triangle. Jim Hall submitted a U.S. Patent (no. 3,455,594) for the rear wing design. Chevrolet engineers Jerry Mrlik, Jim Musser and Frank Winchell were involved in the design. The wing was made of a thin fibreglass skin filled with foam. The radical rear wing made its appearance in the Chaparral 2E at Bridgehampton in September 1966.

APPENDIX 3 – THE FIRST WINGED WONDER?

The 550 Spyder at Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance in 2015. Rewind Media Collection.

Imagine a 550 Spyder with a wing on two sturdy struts bolted directly to the chassis. This 550 had just that once a 22-year-old engineering student at the Zurich Technical University got his hands on a 550 in 1956. Michel May did just that. Additional cross bracing over the driver’s legs added more strength and a lever mounted on the driver’s left actuated the wing via a steel cable. See https://www.collierautomedia.com/porsche-550-spyder-michael-may