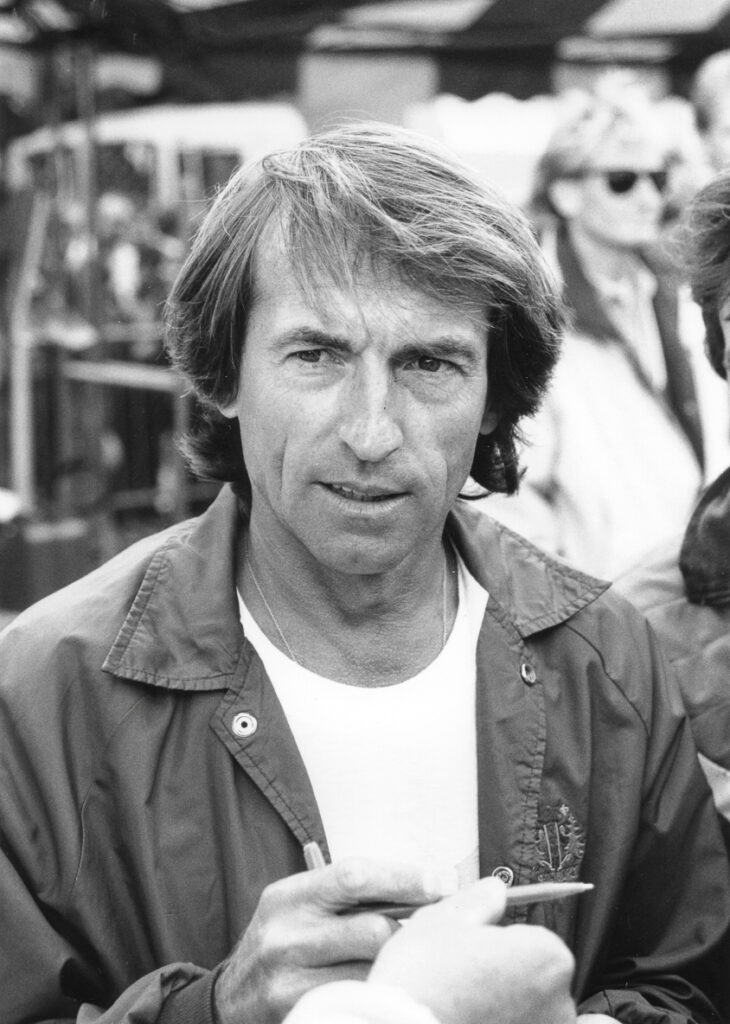

Race driver, manufacturer of wheels for Formula 1 teams, operator of a race school, Mike Knight has been involved in all of these. Few know of the number of champions that his Winfield Racing Drivers School has produced.

Words by Eli Solomon

When I ran the story of the Brabham BT9 that won the second Suzuka International Grand Prix in 1964 [Candy Apple Caper, Rewind Magazine Issue 010], I knew I wanted to revisit the story behind Mike Knight, winner of that race in the Brabham.

Mike raced single-seaters and sports cars competitively around the world from 1963 to the mid-1970s. His vast motor sport experience went well beyond racing in Formula Junior and Formula 3 for which he is widely known.

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to spend a thoroughly enjoyable evening with this gentleman at a French restaurant and pub, The Carpenter’s Arms, in Sunninghill, Berkshire when I was in UK a few years ago.

WINFIELD INCUBATOR

Aside from being the second Briton to have won the Japanese Grand Prix, Mike is, within the French racing community, better known as an incubator of budding race talent. Not much has been written about the successful race school he ran that his father Bill founded in France.

The Winfield Racing Drivers School was named after Mike’s maternal grandmother and not, as some speculated, after a brand of cigarettes. His father’s objective had been “to create a base from which his sons, Mike and Richard, could race.” Bill Knight was a successful land speed records campaigner up to the late 1950s. An exuberant businessman, he regularly used the Winfield name when he set up companies “left, right and centre.”

RECORD SETTERS

To write about the Winfield school without also mentioning Jim Russell, the man who set up his race school (of the same name) earlier, would do injustice to the history of European motor sport. Bill and Russell knew each other well. Bill and business partner Jersey jeweller Arthur Owen (who raced in Japan, Macau and Singapore in the 1960s) were actively trying to break land speed records in various car classes, and they approached Russell, a driver of some success, for a series of joint attempts in the mid-1950s. The trio teamed up and Russell set a series of records in a Cooper sports car for the 50km, 100km and 200km classes in International Class G in October 1955.

Concurrently, Russell continued racing and notched up 64 British F3 wins netting him three British F3 championships in the process. His claim to fame was however the establishment of the world’s first racing school in May 1957. It set the stage for thousands of aspiring race drivers who could now receive formal training to learn to race; the school laid the foundations for modern British motor sports. A young Mike Knight was sent there for lessons and spent winters working on the school’s cars.

Jabby took the old man down to Magny-Cours where this farmer had built this circuit and had no idea what was going on. Dad and the farmer just hit it off; they were fairly gregarious people. It went from there.

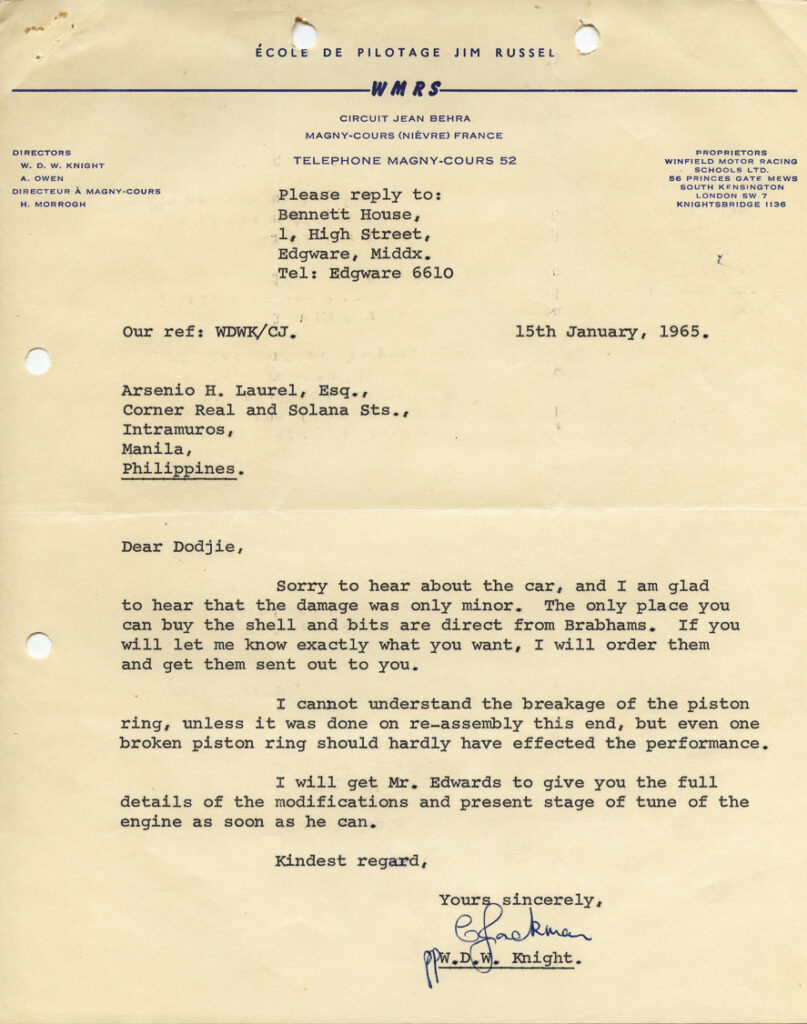

What a Winfield Motor Racing School letterhead looked like in the early days.

’ECOLE DE PILOTAGE

Sensing a viable opportunity in this business, Bill Knight approached Russell to see if he would be interested in setting up something similar in France. A suitable site at Magny-Cours, about 250km from Paris, was located by a mutual friend and well-known French journalist Gerard ‘Jabby’ Crombac. “Jabby took the old man down to Magny-Cours where this farmer had built this circuit and had no idea what was going on. Dad and the farmer just hit it off; they were fairly gregarious people. It went from there. It was a remarkable thing to witness,” Mike says.

Initially called ‘L’Ecole de Pilotage Jim Russell’, the race school was renamed ‘L’Ecole de Pilotage Winfield’ in 1963 when Bill took over the school from Russell. The Winfield school has been associated with such Formula 1 drivers as François Cevert, Jean Pierre Jassaud, Jacques Laffite, Alain Prost, and of course British driver Damon Hill. The school was so successful that in 1971, a second in France was established at the Paul Ricard Circuit; Patrick Tambay was the first winner of the school’s racing competition. Tambay, who raced at the Malaysian Grand Prix in a Theodore Racing March 752 in 1977 and slashed the lap record in the process, would go on to a successful career in Formula 1, competing in 123 Formula 1 Grands Prix.

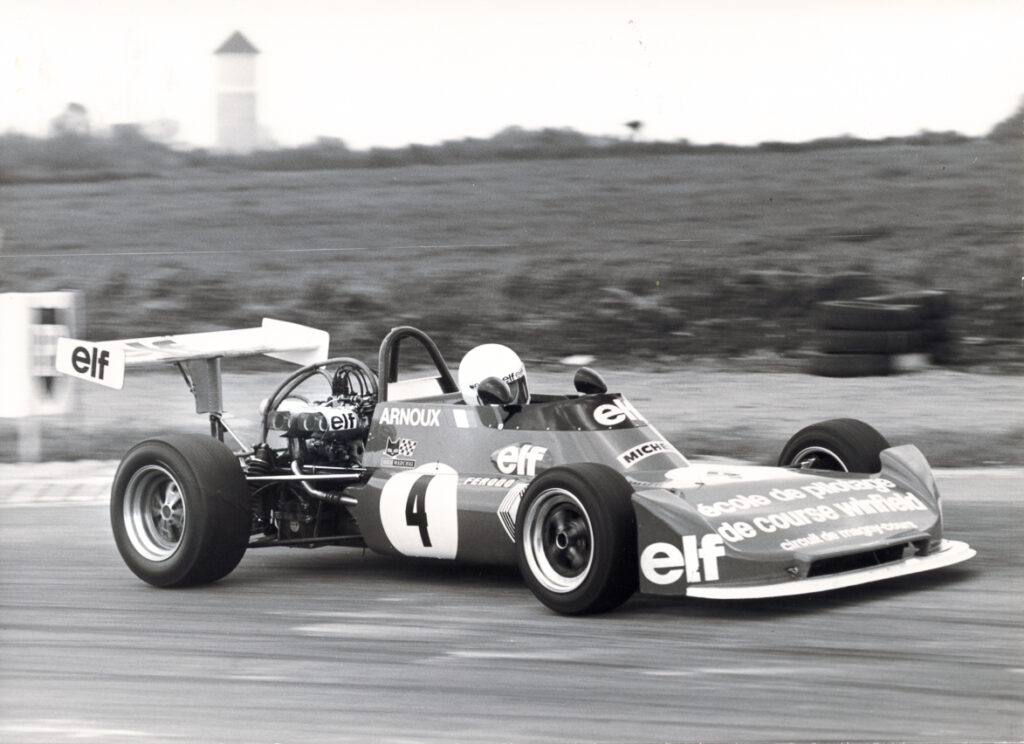

Frenchman René Arnoux was the last of Winfield’s Volant Shell scholarship competition drivers. He would progress on to race in Formula 1 with Tico Martini in 1978.

FIRST RACE

Mike has himself had a fair bit of racing experience which stood him in good stead as an instructor at the Magny-Cours school which he ran from 1966 until 1973. He won his first race in 1963 in a Lotus 23 when he narrowly beat fellow countryman Chris Irwin in a Merlyn Mk6. “We had a hell of a good race and I was a little bit disappointed afterwards to find out that his Merlyn had a 1000cc engine while my Lotus had an 1100cc and I was really struggling to beat him,” he tells me modestly.

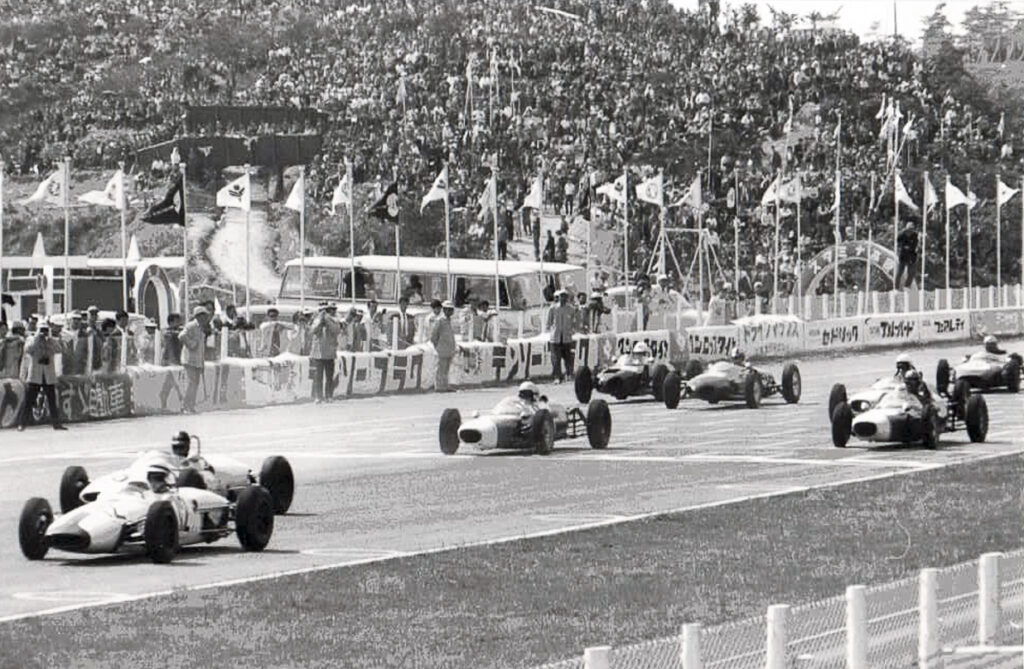

I refer him to his victory at the second International Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka in 1964 in his Brabham BT9 Formula Junior (see upcoming BATTLE OF THE BRABHAMS). With only a couple of short snippets in Autosport Magazine describing the two events in Suzuka in 1963 and 1964, I was keen to find out how it all came about.

Mike explains that Crombac and his father got involved in sending a group of race cars to Japan for Suzuka’s first international Grand Prix in 1963 (the Suzuka Circuit opened a year earlier). “Jabby put together that first race in Japan in 1963. Jabby was also responsible for getting the Magny-Cours circuit in France for Dad. They were very friendly. They were both sort of party boys and Dad had done quite a lot of land speed records in France and got to know Jabby quite well. I believe Jabby was asked to get some cars together from Europe by the JAF,” Mike says. It was quite an undertaking to get a posse of well-known English names to Japan.

There were quite a few illustrious names that went the first year. Arthur Owen was looking into a possible business venture of importing Honda cars and bikes into Britain and so the Japanese trip served his interests. Other drivers included Peter Warr (joint Managing Director of Lotus Cars), John Greene, Tiny Littler, Mike (Lord) Louth and Arsenio ‘Dodgie’ Laurel from the Philippines.

The Asians who raced there were no match for Warr and his Lotus in 1963 or Mike in his Brabham in 1964. Mike was over the moon with his victory which came at a point when he was straddling his accountancy studies with his racing.

The British drivers pose by the Ben Line cargo liner prior to boarding the vessel for Japan. Bill Knight organised the trip. Mike Knight’s Brabham BT9 is in the centre.

“Flying out there was quite a big thing,” he recalls, and he had a great time in Japan. “One of my best memories was being surrounded by a bunch of Japanese school kids. I was considered to be quite tall out there. I said, ‘Hello, how’s it all going?’ to this lot of kids and they absolutely collapsed with laughter and mimicked what I’d said, which sounded like gibberish. That’s how English obviously sounded to them. It was hysterical.”

A chance introduction to a “very nice Japanese girl” gave him a better understanding of the Japanese culture. “I was invited into people’s houses where you sat on the floor and took your shoes off. They were desperately concerned that I was going to get involved with their daughter,” he chuckles.

There was an eclectic grid of Formula Juniors at the 1964 Japanese Grand Prix in Suzuka including entries from Hong Kong, Malaysia and the Philippines.

THE FORK AHEAD

Formula 3 racing was just picking up at the time and Mike jumped in with both feet. “I had a couple of good races after getting back from Japan and I won the Leinster Trophy in Dunboyne and the Mike Hawthorn Trophy at Phoenix Park in the BT9. David Piper had also won that trophy and later remarked to me, ‘If you did that, you can’t be half bad then.’”

Mike’s father Bill was close to race car builders Charles and John Cooper. In 1965, the Knights acquired a Cooper T76 because Bill insisted on one; everybody else had Brabhams. “I insisted we put in a Cosworth MAE engine. I didn’t want that BMC thing inside,” quipped Mike. Despite the new purchase, racing was going to take a major backseat to business.

By 1966, the race school was starting to take up too much of Bill’s time and had yet to turn in a profit. His father made Mike a proposition. “I had just done my intermediates in accountancy and it was quite difficult to race and work. Dad said, ‘You’ve got six months. If you can turn this thing around and get it going, then we’ll have a deal. You and your brother can buy it off me and you can take it on.’” Mike immediately realised that putting fees up 10% would make a big impact on the bottom line as there was no lack of racing aspirants. “And away we went!” he says. At this point, Mike’s racing was no longer funded by his father and the Winfield School bore the burden of this.

Tico Martini was Winfield’s first Chief Mechanic in 1964 before he became its Chief Instructor. He founded Automobiles Martini in 1965. His first single-seaters used at Winfield looked remarkably like the Brabham BT21.

The brothers wanted to take the business to a new level. Mike elaborates, “The guy who was running the school with me was Tico Martini. Of course Tico went on to build the Martini race cars. Tico and I were the instructors and we’d got English instructors; that was one of our secrets. Jim Clark, Graham Hill, Jackie Stewart, they were all the stars, so anyone who spoke English and who was involved in motor racing must know what they were doing. The French fell for that. Jabby had organised some sponsorship for us that we would never have got ourselves. It was quickly recognised by the French as the place to come for driver training. We ran it well – there was no favouritism. You either could do it or you couldn’t.”

By this time, the school was doing quite well and kept Mike occupied until 1973 when he returned to the UK. Mike’s brother Richard moved to France and took over the business for the next ten years before Mike returned again in 1983.

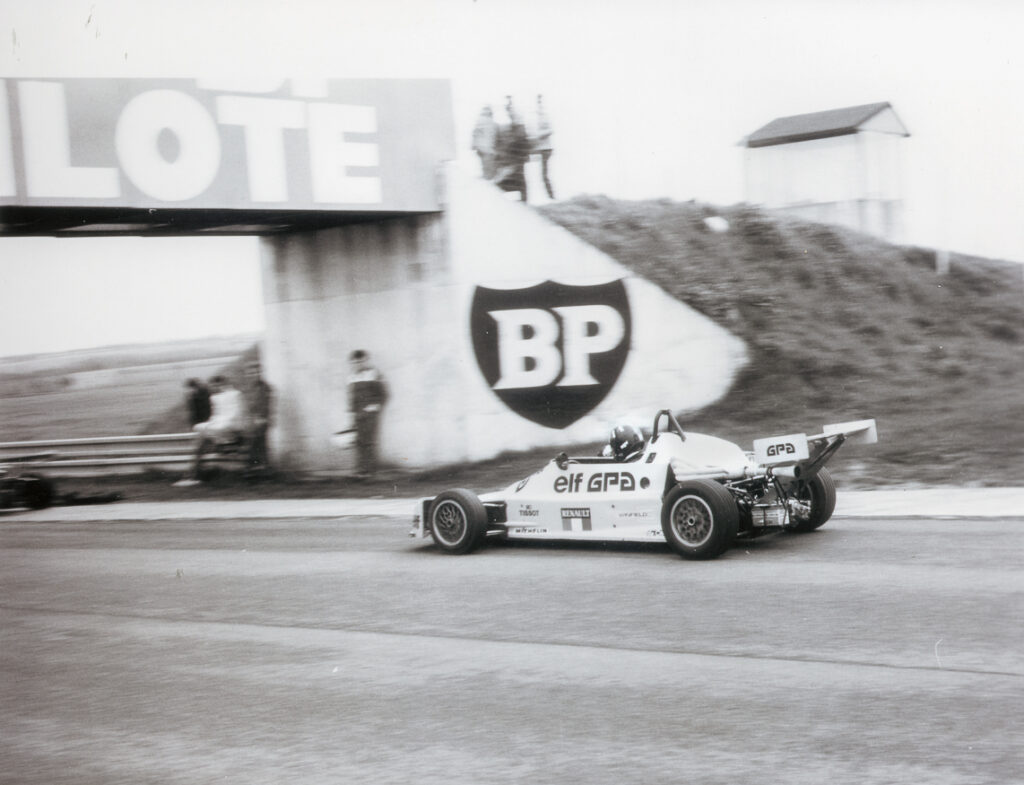

The Winfield school was one of the great British institutions abroad. By 1973, Winfield’s first school at the Magny-Cours Circuit was supplemented by another at the Paul Ricard Circuit.

WINFIELD NURSERY

Mike and Richard operated the school at the Magny-Cours Circuit from 1963 to 1973 which was backed by sponsorship from Shell. When Frenchman François Cevert died of injuries sustained in a practice accident at Watkins Glen in October 1973, Shell pulled out of the program as world economies took a beating from the first oil crisis.

Frenchman René Arnoux was the last of the Volant Shell scholarship competition drivers. It was however not the end of the road for the school. French oil giant Elf picked up interest in the sport on home soil just as Winfield expanded to a second school at the Paul Ricard Circuit at Le Castellet, near Marseille, and Elf became the new sponsor.

Our drivers were just Hoover-ed up straight away. They became professionals before they knew what had hit them.

The Winfield schools have had a solid reputation of having groomed a very large number of Formula 1 drivers. Mike proudly tells me that they had 30 Formula 1 drivers graduate from the two schools over a course of 35 years. There were two main reasons for this: The first was that both the circuits where Winfield operated had a good reputation. The second and more important reason was that French tuner and race car builder Alpine and conglomerate Matra were just coming in to the race car development scene and were looking for quality drivers to test and race their latest creations. “Our drivers were just Hoover-ed up straight away. They became professionals before they knew what had hit them,” Mike tells me.

WHEELS OF CHANGE

Mike’s break from the race school enabled him to set up a die-cast wheel business for motor sports. “We were the first to do die-cast magnesium wheels called the DYMAG wheel. We supplied virtually every Formula 1 team,” he informed me. When he eventually sold the business in 1983, Ferrari was the only Formula 1 team that had not used DYMAG wheels on their cars.

The DYMAG business kept Mike in touch with the movers and shakers of Formula 1, everyone from Ron Dennis to Frank Williams. In the 1970s, neither Ron nor Frank were well-funded and it became habitual for Mike to visit the factories asking for payment.

He recalls, “I would have to go around asking people if they’d be so kind as to pay us for the wheels, and amongst them, Ron. I remember swimming through this deep, white carpet of his which he had in this immaculate workshop in Woking. I’d say rather impolitely, ‘Ron, don’t you think you could pay for the wheels before we bought this carpet, don’t you think that would be alright?’ I remember him saying, ‘You don’t understand, Mike, you know, the next guy who comes through the door could be a sponsor who could really take us places.’ Yes, yes, yes, now where’s the cheque? But look where he is and where we are. He learnt something way, way faster than most people.”

Damon Hill in one of Winfield’s cars in the early 1980s. He arrived for the Winfield course with his father Graham Hill’s iconic helmet.

HILL SPOTTING

Mike returned to France to run both Winfield schools in 1983. It was then that he embarked on internationalising the business. An influx of English instructors was the start. Until then, the students had been mostly French. One aspiring yet very unassuming racer arrived at the school for instruction. His name was Damon Hill.

“I did a deal with Damon’s Mom to help him through the course. Remember, Damon was only 14 when his father Graham died. When Damon came down to the school, it was an extraordinary thing because he came from motorbikes. He didn’t start on cars till he was 23 or 24, so he came to the school knowing nothing about the current scene at all,” Mike revealed.

Hill “turned up sort of incognito, but with his father’s crash helmet, one of the most iconic and recognisable helmets which everyone knew. He’d only come down because his mother had wanted him off bikes and to try cars.”

Hill, it transpired, quite enjoyed the training but he was up against others “who’d been dreaming of winning this [scholarship] drive in France, like winning Indy to an American,” says Mike. “That’s how entrenched this system was. We had six-day courses. Damon never really stood a chance.

We just didn’t know how good or not he was going to be, which was quite frustrating for us. He did the six days and qualified for the semi-finals, but there was no way he was going to make the final. He was a tidy driver, but a second off the pace. His reaction was surprising. He told me he was terribly disappointed. He doesn’t reveal much but he was visibly upset by the results. It was a good sign.”

Those who knew his world champion father Graham Hill remember him doggedly working away on test days before he would be comfortable with circuit and car. “That’s exactly what Martin Donnelly said about Damon. He would never stop testing until he was quicker,” Mike revealed.

In 1983, the Winfield schools organised a special four-day course for international students. It was limited to just six students at each school. The best driver on each course received the Winfield Trophy award, a scholarship to progress to the Advanced Course.

Mike and Richard were in the position to witness some of the very best drivers of the world emerge. “We had 60 guys win these scholarship drives over the years. Thirty of them made something of it and thirty didn’t. It was a pretty high hit-rate but it was also quite a high failure rate as well. It was always interesting watching what made the drivers stand out, what made Arnoux or Prost stand out.

Well, Prost was an exception.” Mike elaborates, “Generally speaking, it wasn’t just about the driving. A lot of these guys were very, very good. But there’s something mental that is required, and sometimes you can see it and sometimes you can’t.” Sometimes, it took another instructor to see what Mike or Richard could not see. “I always remember Tico Martini saying of François Cevert, ‘that guy is going to be in Formula 1 in a few years’ time.’ This is 1966 and I’m François’ instructor. He’s my age. I still remember telling Tico, ‘I’m sure you’re right, but I don’t know why really,’” Mike says.

Alain Prost went on to win the French and European Formula 3 championships before joining McLaren in 1980 at the age of 25.

It was obvious that Prost would go far. “We had the school and when they graduated, we had the Formula Renault team which we ran. And we’d get them out of the Formula Renault team and into the Winfield Formula 3 team. We won the French Formula 3 championships maybe 5 or 6 or 7 times. The first season Prost pitched up to my brother for the first race, he walked around the paddock, came back and boasted that he could win the race.

Richard was a little less convinced. ‘Christ, what have we got here if he’s thinking like that? We’ve got a problem.’ Sure enough, Prost won the race, and went on to win the next 12 races in his first season in Formula Renault in 1976. Twelve races, twelve wins! He was leading the thirteenth race when the gearbox broke, so he didn’t have a clean sweep,” Mike recalls.

Prost was extremely focused on his racing. Mike relates, “I’m having a chat with him and it still hadn’t dawned on me how competitive he was. He was testing a Formula 3 car and we were talking about gearboxes. He said, ‘The thing, Mike, what you’ve got to remember about gearboxes is you think about how you’ve got to look after them, you think about how many points you could lose by breaking gearboxes over a career.’ I remember sitting down and thinking: this is what differentiates a champion from others. That’s why these guys are where they are.”

Later, when Prost was asked what advice he would give a young aspiring race driver, he would answer, “Work out what championship you can afford to compete in, and then work out how you are going to win it.”

Alain Prost entered for the Volant Elf competition at the Winfield School at Paul Ricard in the autumn of 1975 and emerged with a Formula Renault prize drive for 1976. He totally dominated the French Formula Renault championship season and walked away with the championship having won all but one of the races he entered. He would go on to win four Formula 1 world championships and run his own Formula 1 team.

Jacques Laffite was a graduate of the Winfield School at Magny-Cours. He would go on to a successful career in motor sports.

What do you mean? I’m either going motor racing or I’m going fishing, there’s no problem. I fish very well.

Jacques Laffite

Having seen these young aspirants put through the paces at Magny-Cours and Paul Ricard, did Mike think he had the skills or harbour aspirations to race in Formula 1? “I was there or thereabouts from the driving standpoint. When it came down to it, Jacques Laffite put it best. I asked him what he was going to do if motor racing didn’t work out for him. He replied, ‘What do you mean? I’m either going motor racing or I’m going fishing, there’s no problem. I fish very well.’ I could not think that way.”

While Formula 1 may not have been something he or Richard considered, both were fond of racing. Following a stint in Formula 3, Mike continued to do a few endurance races, including the 24-hours of Le Mans with Richard and Frenchman Christian Mons in a 2-litre March 75S in 1975, with sponsorship from Madison Beef Burgers.

When I visited him on my way to the Goodwood Revival, Mike and good friend and fellow historic racer David Piper were off to Warsaw for a historic demonstration round the streets of the city in one of David’s many exquisite historic race cars. They were also casting furtive glances at Suzuka, cooking up something for the circuit’s 50th anniversary since its first international race.

Hi, I was one of the international students that attended the School in Magny Cours. I was a naive 19 year old motor racing fan who had a dream of becoming a racing driver. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and found Mike and his brother Richard to be true gentlemen. I can still remember some of the stories he would tell us over dinner. Great memory, and very pleased to see Mike looking so well. Winfield racing drivers school has a very important place in the history of motor sport and it is great to see it back on the scene at Paul Ricard. Regards to everyone associated with it. Paul.

Thanks for your post Paul. Always good to hear first hand accounts. Really appreciate your contribution. Keep ’em coming. Eli – [email protected]

Merci c’était très intéressant et bravo pour

Toutes ces années de sport automobile !!