The Early History of Cycle & Carriage

Last Updated 23 December 2021

Motor traders are a conditioned lot, often at the mercy of the regulatory environment and the fickle taste of buyers. One company has evolved from humble beginnings and grown over the past 112 years to become one of Asia’s leading motor distributors. In this first of a two-part special, we chronicle the extraordinary developments in the early history of Cycle & Carriage.

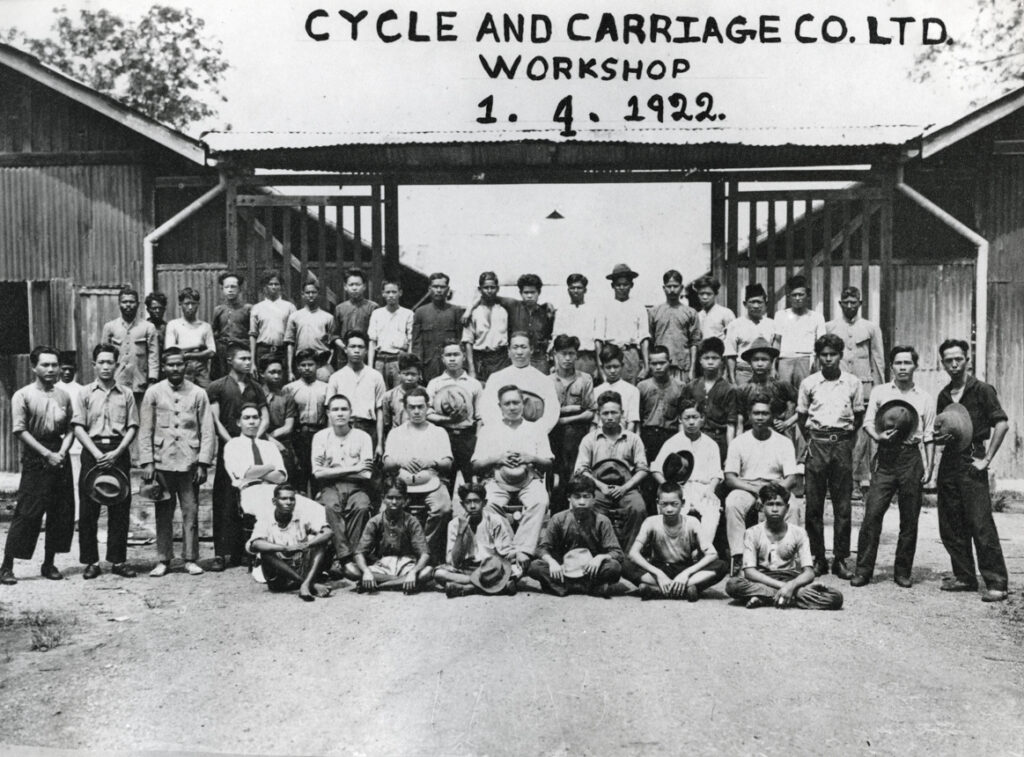

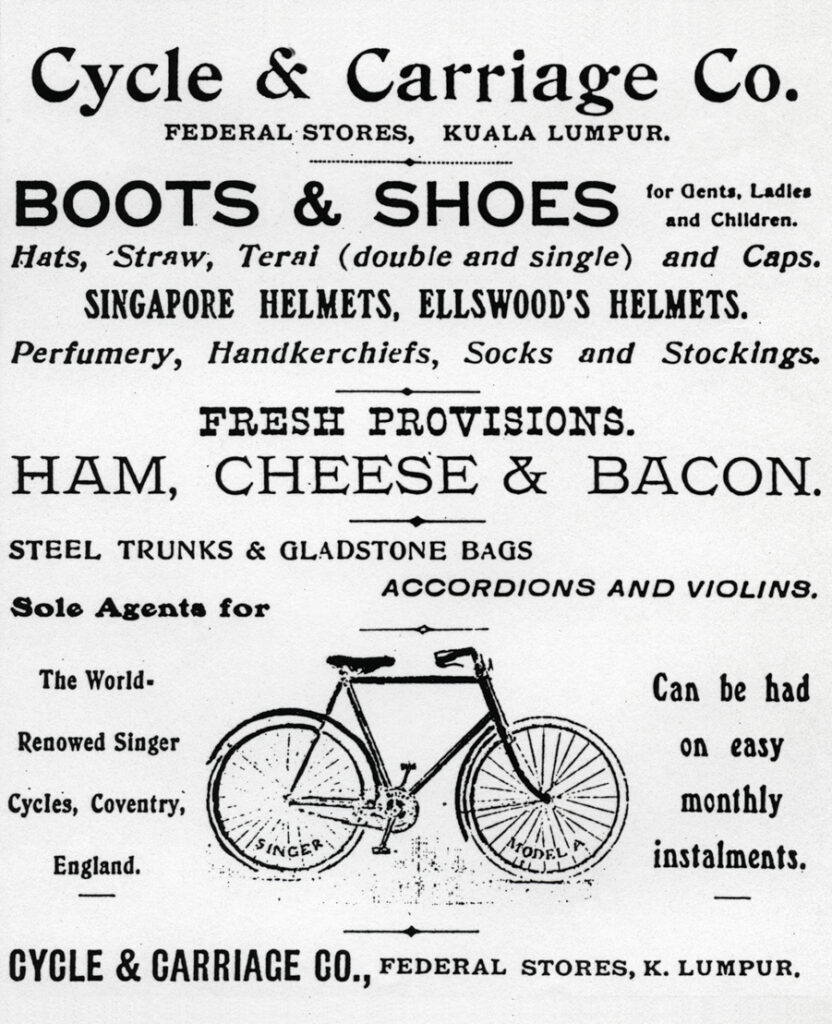

It started from modest haberdashery beginnings in 1899. The company, Cycle & Carriage Repairers, Painters and Varnishes, sold bicycles, cycle accessories and even golf clubs. The automobile was a new and unknown contraption then. Transportation was still dependent on the horse, carriage and rickshaw.

An inconspicuous advertisement appeared in the Malay Mail papers in Singapore in early August 1899 – Cycle and Carriage Co. (C&C) was registered for business on 15th July 1899 at No.159, High Street, Kuala Lumpur. The Company was set up by the Chua family. Two of Fukien immigrant Chua Toh’s five sons, Chua Cheng Tuan and Chua Cheng Bok, had worked for Riley, Hargreaves and Co., one of the region’s earliest engineering companies. The brothers left to form Federal Stores, general merchants in the Federal Capital, Kuala Lumpur. From this came C&C. Soon after, all five sons became involved in the business.

1900s-1920s – HAM & CHEESE, TYRES & CHAI

1900s-1920s – HAM & CHEESE, TYRES & CHAI: Rapid growth of the road network in the major mining and commercial towns in Malaysia (then Malaya) resulted in strong demand for heavy equipment and consumables. C&C carried a wide variety of products. By 1906, the Company was retailing Dunlop motor car tyres. That year, a branch at Brewster Road in Ipoh was established. By 1912, C&C were sole agents for various motor and bicycle brands – Albion, BSA, Singer, Monopole, and Opel.

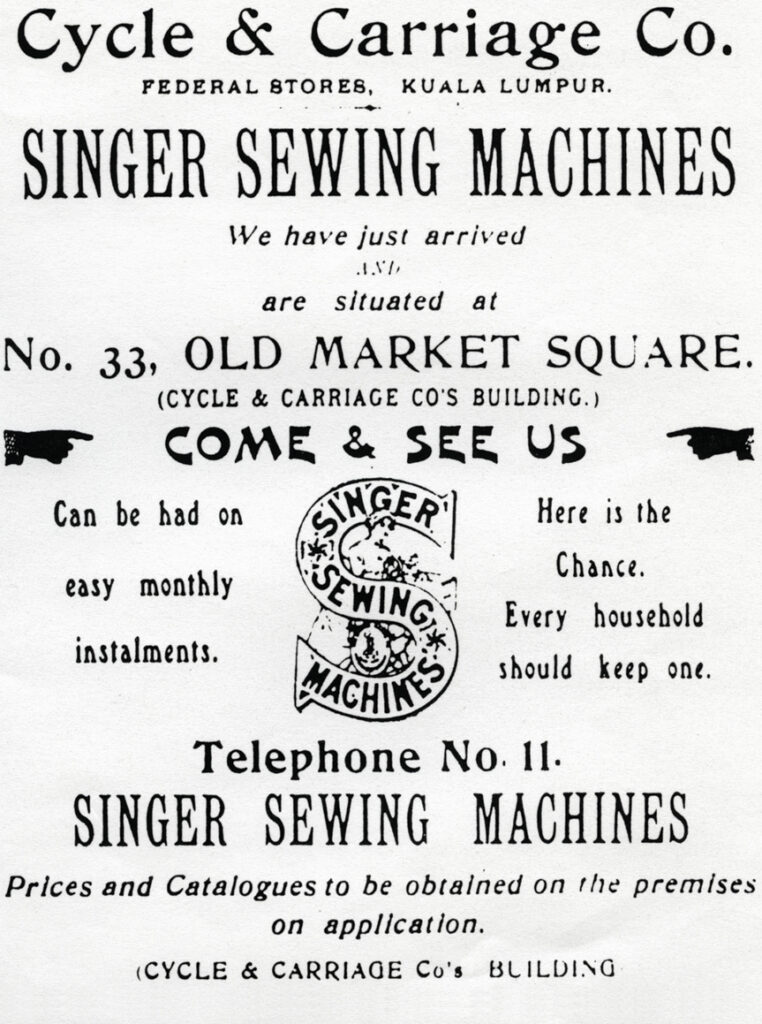

The Company also dealt in all manner of estate tools such as guns, revolvers and cartridges. It also sold Ceylon Tea, for which the Company was sole agent within the Federated Malay States (FMS). Top selling products included Singer bicycles and sewing machines. C&C also acquired Kuala Lumpur’s ‘mosquito’ bus service, giving it the largest fleet of busses operating in Malaya.

Reflecting C&C’s growing prosperity, a state-of-the-art three-storey office equipped with an “electric lift” was built at Bishop Street in Penang in 1914. In 1916, the Company opened an office in Singapore at 193-195 Orchard Road; it later moved to 3 Orchard Road by 1922. By 1918, C&C was converted to a Private Limited entity called C&C Co. Ltd. incorporated in the FMS with a capital of $250,000.

Most of the cars C&C sold during this period were American. These included Chandler, Cleveland, New Overland, Willys-Knight, Hudson-Essex and Paige. The fortunes of the motor industry in Malaya fluctuated with that of the local rubber and tin markets, and while the Company made profits after the First World War, losses were posted for 1921 and 1922. Consolidation amongst global car manufacturers was rife during this period, but demand for vehicles in Britain’s colonies was strong. An agency positioned its stock of cars according to the economic conditions of the period, especially emphasising the economy of its cars in lean years. Vehicle sales was a major part C&C’s business at this juncture.

1920s-1940s – WINDS OF CHANGE

1920s-1940s – WINDS OF CHANGE: On 18th May 1926, the Company incorporated C&C Co. (1926) Ltd in Singapore with a capital of $5,000,000. The business focus was gradually moving to Singapore and in that year, C&C sold 643 new cars, 144 new motorcycles and 33 used cars. The four brothers (Chua Cheng Tuan had died in 1912) had spread themselves across the Peninsula with Chairman Chua Cheng Bok and Chua Cheng Hee based in Kuala Lumpur, Chua Cheng Liat in Penang, and Chua Cheng Hock in Singapore. The Company’s board consisted of pillars of society and industry heavyweights Lim Chin Tuan, Tan Cheng Lock, John Middleton Sime and Richard Page – a who’s who of Far East commerce at the time. Its list of agencies encompassed British, French, Italian and German brands.

The local big trading houses such as Katz Brothers, Behn Meyer, Guthrie & Co, The Borneo Co., C. Dupire & Co., C.F.F. Wearne, Garland, and United Engineers were all involved in importing cars and commercial vehicles. After the First World War, more and more British and continental brands began to make their appearance in Malaya. C&C quickly expanded its range of agencies, but joy soon turned to gloom with the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s. In May 1930, both Sime and Page resigned from the board. The Penang and Ipoh offices closed down in 1932. The price of tin had fallen to £100 a ton in 1932 from £284 a ton in 1926. A swift turnaround in the tin industry was not expected, so too the fortunes of the motor trade tied so closely to this industry.

By 1934 however, there was a renewed sense of optimism as was reflected in the British Trade Fair held in Singapore. Demand for consumer goods, including cars, was picking up. C&C made a small profit in 1935. The Company had taken over the Renault agency from Guthrie. Its BSA agency was doing well with a range of light cars called the Scout, and it was promoting Willys cars which were reputed for their economy. Car importers began to spend on renovating offices and showrooms, and on advertising.

But by the late 1930s, there were ominous signs of war in Europe. Malaya would become the ‘dollar arsenal’ for the British Empire, and the country ran its rubber and tin mines at maximum utilisation levels in exchange for hard currency. By the start of the new decade, it became clear that South East Asia was not immune to an invasion. With the Japanese military juggernaut advancing towards Malaya, many of the local companies began dismantling plant and equipment in preparation for war, some destroying all company records in the process. A young nephew, Chua Boon Unn, who was serving his apprenticeship in the Company when war broke out, recalled selling ice cream in a confectionery shop for a living during the period. C&C’s Chairman Chua Cheng Bok died on 25th April 1940 in Ipoh, and in May, Chua Cheng Hee assumed the position, a role he held until his retirement in February 1949.

By 1948, business had picked up sufficiently for C&C, with its base in Singapore, to look at acquiring more agencies. Jowett cars and Bedford commercial vehicles were added to the stables. After a decade at the helm, Chua Cheng Hee made way for Chua Cheng Liat, the youngest of the five brothers, to take over as Company Chairman. This marked a major turning point in the fortunes of the Company.

1940s-1960s – WHEELS OF FORTUNE

1940s-1960s – WHEELS OF FORTUNE: Early post-war vehicle production around the world was virtually non-existent; Britain and Europe had been decimated. The Americans, however, were quick to resume operations, and by January 1948, several brands were already advertised in Malaya. That same month, an updated version of “The Motorists Guide” was published; it revealed much improved consumer sentiments. The British motor industry quickly ramped up production of their new models. For $3,560, one could purchase a new Ford Prefect; the popular MG TC sports car cost $4,015; and a Humber Pullman limousine set the affluent buyer back $12,795.

C&C was offering a new 1-litre British-made Renault Eight, the French maker’s first post-war model, with short wave radio and all leather upholstery. In 1949, there were a total of 49,000 vehicles on the roads in Singapore, 30% of which were cars. Singapore’s population had doubled since 1931 and was now just under a million.

When agency house Brinkmanns Limited began winding down its local operations in 1950, it presented a golden opportunity to the astute Chua Boon Peng, eldest son of Chua Cheng Liat. Coming across a handbill noting an auction of Brinkmann’s stock of Mercedes and Jaguar cars, he approached his fellow directors to recommend securing both agencies from the principals. Younger brother Boon Unn recalled that they “literally had it thrown at [them] because the executives of the former agents simply packed up and went home.”

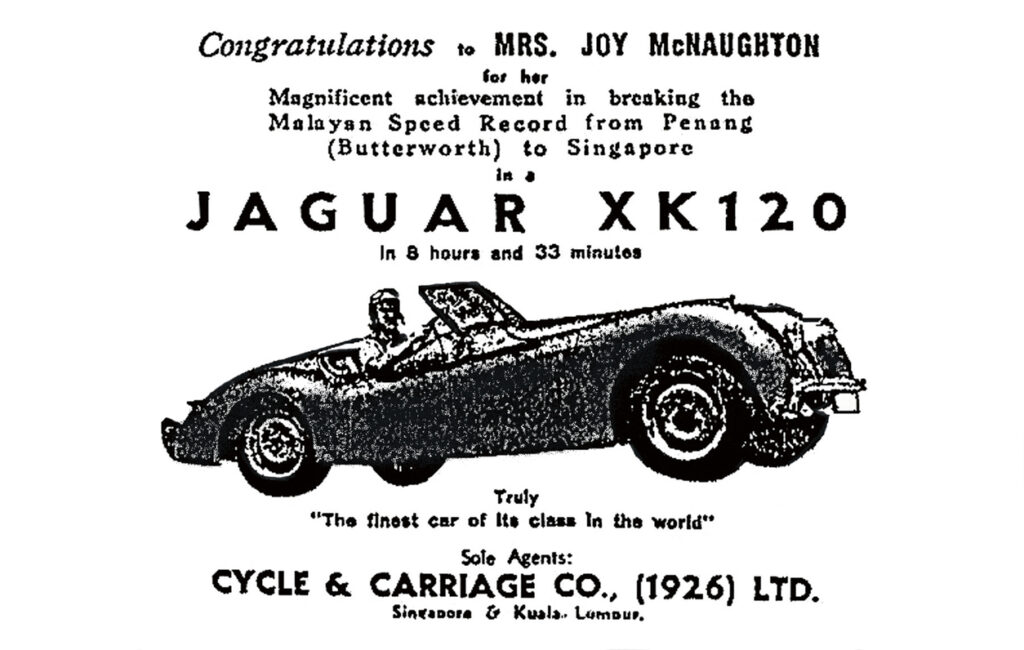

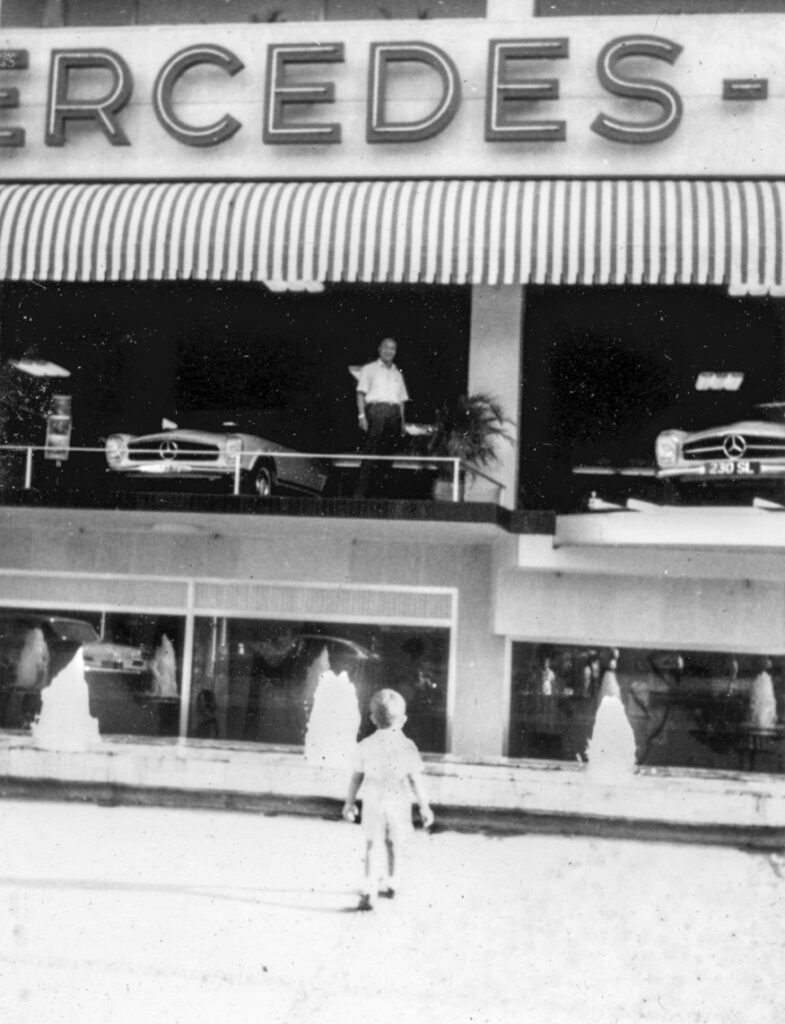

The Jaguar sole-distributorship was obtained in July 1950; Mercedes-Benz came a year later. It proved to be a master-stroke. Overnight, the family-run business became one of the major premium automobile market movers in Singapore and Malaysia.

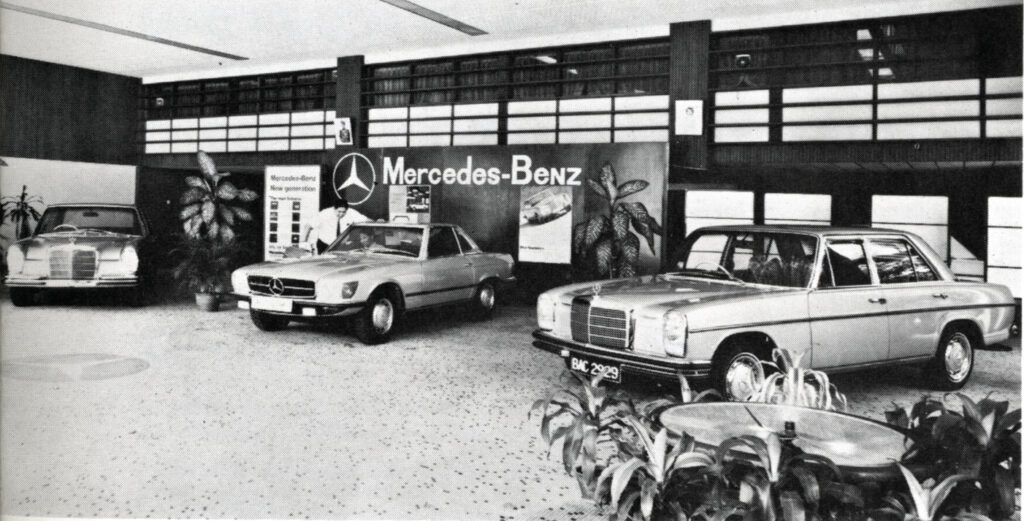

The youngest son of Chua Toh would remain at the helm until his untimely death in 1957. Chua Cheng Liat’s sons, Boon Peng and Boon Unn, had already assumed important roles in the Company and consolidated the Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar franchises, making these a big part of the Company’s business. Boon Peng became Chairman, Boon Unn, Managing Director. Mercedes had a reputation for making indestructible cars that were best suited for “fleet” use in the region. The Mercedes diesel 170D became the model of choice for taxis in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, with no loss to the prestige of the brand.

The luxury car market was growing too. Jaguar offered attractively-priced saloons and sports cars; an XK120 Roadster was priced at $10,800. The Mercedes-Benz range included the 170SV saloon and the 220 ‘Ponton’, priced at $8,500 and $12,275 respectively. In 1957, the price of a Mercedes-Benz 300 saloon was $35,000, the same as a newly-completed 3-bedroom bungalow off Holland Road in Singapore. Buying second-hand was always an option. A used Mercedes-Benz 220 ‘Ponton’ could be bought for under $8,000 with up to 70% loan financing. C&C also held the agencies for Plymouth, Hudson and the much cheaper Singers.

Car buyers were spoilt for choice as manufacturers unleashed new models at an astonishing rate. Between 1951 and 1961, Singapore’s car population trebled from 22,678 to 70,108. For the next five years, the car population grew by double-digit percentages annually. In 1963, every twenty-first person in Singapore owned a car. The population was 1.79 million and there were 520 miles of road on the island. C&C was riding on a very buoyant wave.

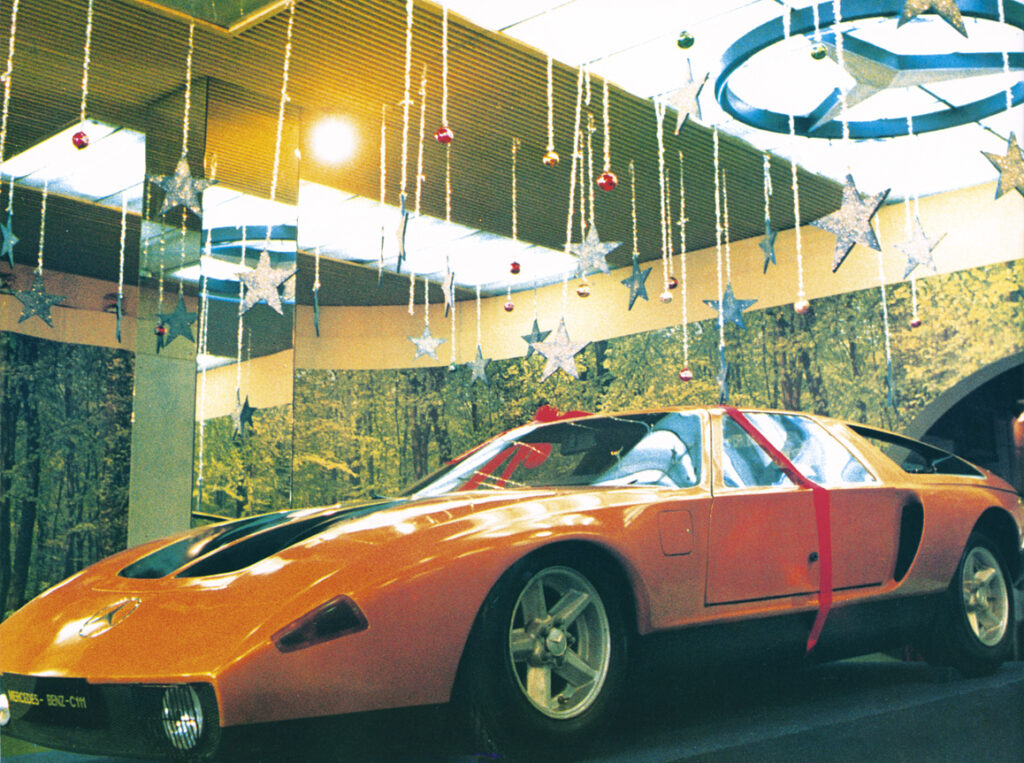

By 1964, the Company had separate divisions dealing in vehicles, parts and accessories, and trade. Aside from Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar, C&C had the agencies for D.K.W. and Auto Union, Plymouth, Chrysler, Imperial, Simca, Fargo – trucks and busses, Willys – jeeps and station wagons, BSA – motorcycles, and even Trojan bubble cars (bubble cars were still hip then). It also sold shock absorbers (Bilstein), pistons (Mahle Komm), lubricants (Bardahl), seat covers (Admis), audio equipment (Becker), diesel engines (Maybach-Mercedes-Benz), battery chargers (Sun and Varta) and tyres (Seiberling). Association with Daimler-Benz had put C&C in a commanding position to cover every aspect in the automobile sector.

1960s – COMPLETELY KNOCKED DOWN

1960s – COMPLETELY KNOCKED DOWN: The entire complexion of the motor trade was however soon to change yet again. From 1963, the Malaysian Central Government’s blueprint for developing the local automotive market encouraged local manufacturing production; tires, cushions, electric cables, batteries and paints were all already being manufactured in Malaysia and Singapore. Singapore followed suit with a similar policy.

In Singapore, Finance Minister Lim Kim San announced a formula “to ensure the establishment of vehicle assembly plants of economic size, and to keep the cost and prices of vehicles assembled locally at the lowest possible level.” An import duty of 30% was levied on imported cars. Local assemblers received incentives such as tax holidays and “Pioneer” status. Every manufacturer wanted to establish an assembly plant on the island. As one local car executive had put it, “If my principals do not agree to local assembly, I am sunk. Kaput. Out of business.” Early in 1964, C&C put forward plans to set up a vehicle assembly plant on the island.

Independence for Singapore in 1965 posed a new set of issues for motor traders. The umbilical cord with the Malayan hinterland now included an immigration checkpoint. Companies rushed to restructure.

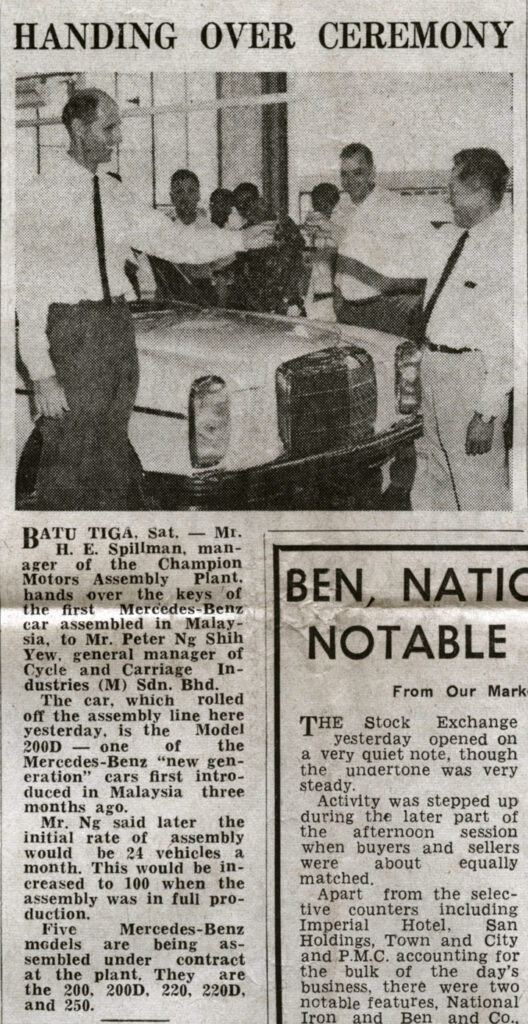

From 1965, Cycle & Carriage Industries, the assembly arm of C&C, began assembling Mercedes-Benz passenger vehicles at the Company’s Hillview Avenue plant off Upper Bukit Timah Road. Four and six-cylinder 190 and 220 fin tails were built from Completely-Knocked-Down kits (CKD). From July 1967, this was extended to the new 250S and 250SE models. By April 1968, the $4-million plant was expanded to build 400 cars per month, including contract work for Volkswagen Beetles and vans. In 1965, it took 250 man-hours to assemble a single vehicle.

By the middle of 1968, this had improved to 170 man-hours, which was superior compared to the non-automated plant operated by Daimler-Benz in Germany. The same year, C&C secured a deal to assemble Mitsubishi cars, and work started at a plant near Tampoi in Johor. A new relationship with the Japanese manufacturer was about to take off.

The assembly business required huge amounts of capital and in 1969, the board felt it was prudent to tap the financial market for capital with a listing on the Singapore Stock Exchange. C&C Limited (CCL) was incorporated that year to acquire the shares of C&C (1926). Managing Director, Chua Boon Unn, was aware that as a growing business, the Company was still perceived negatively as a family-run entity, and seeking a public listing would mitigate this and provide a fresh infusion of funds necessary for its motor assembly operations. The public listing coincided with the 70th anniversary of the Company. Although branches of the family still retained substantial minority interest, the listing effectively reduced their collective control in the Company.

CCL was now irrevocably linked with Mercedes-Benz. The new Jaguar XJ6 model was received poorly locally, and in July 1969, the Company offered their Jaguar franchise to competing importer Wearne Brothers. Dickie Arblaster, the industry enthusiast credited with bringing the Mini to Asia while working with Borneo Motors, was convinced it was a good deal for his new employers, Wearne Brothers, and consummated the franchise in January 1970.

1970s – THE MOTOR MILLIONS

1970s – THE MOTOR MILLIONS: The 1970s was a period of great anxiety for the local economy and motor firms who had spent millions on establishing their factories. Several global events would impact the local motor industry adversely. These were the British military pull-out of Singapore in the early 1970s, the devaluation of the Pound Sterling and the end of the international Sterling Area in 1972 that meant that the Singapore dollar was no longer wholly-pegged to the Sterling, and the first oil crisis in 1973. Nonetheless, Singapore’s accelerated plans to industrialise meant continued and robust demand for industrial equipment and machinery from manufacturers such as Daimler-Benz.

Against the backdrop of tougher worldwide emission and safety laws, global automakers were having a difficult time coming up with unique designs for the mass market. It became clear that the closed-door assimilation taking place among manufacturers (such as at British Leyland and at Fiat) in the name of survival had resulted in cars looking suspiciously similar; it prompted respected motoring journalist and scholar Leonard Setright to cynically remark that “if there were not many fathers, there were plenty of mothers.”

By the mid-70s, one in seventeen people in Singapore had a car, and the population had risen to 2.25 million. There was now 1,200 miles of road on the island, more than a two-fold increase since the early 1960s. The peak of the decade was in 1973 when there were 188,000 cars and 123,000 motorcycles registered on the island. A Mercedes 200 assembled by CCL was 20% cheaper than a BMW 2002 Tii imported by Continental Motors. CCL had the largest market share in the over 2-litre segment.

With the rapid growth of vehicle population in the country however, the Singapore government began to take a hard look at ownership as well as usage of cars. In 1975, there were two hikes in road tax and an increase in the additional registration fee for imported vehicles. The local motor firms could not have planned for this. The trade took a beating. New car registrations fell 43% year-on-year from 11,839 in 1974 to 6,702 in 1975. No recession had such an impact on the purchasing power in the country. The car population fell from 139,950 in 1975 to 133,350 in 1976 and to 132,064 in 1977. Singapore’s road tax was the highest in the world.

In 1977, CCL listed its subsidiary company Cycle & Carriage Bintang (CCB) in Malaysia, diluting its stake to 70%. That year, CCL began retailing Mitsubishi cars. Within the year, the new Mitsubishi Sigma model had become a strong seller, garnering 17% market share for CCL in 1978. There was evident concern that the Singapore government would introduce even more stringent measures to restrict car ownership in the country. When Ong Teng Cheong, then Senior Minister of State (Communications), presented a paper to the Singapore Institute of Planning in March 1978 titled, “A Nation for Cars or People?”, it clearly stated the government’s case that car owners would pay dearly for owning a car.

In 1979, matters went terribly pear-shaped for the assembly business when the Singapore government withdrew its tariff protection for local assemblers. CCL and Ford, the two largest assemblers, lobbied hard but unsuccessfully for a reversal. The door was now thrown open for equal competition for imports from companies like BMW and Toyota. With 70% of the automobile luxury segment of cars 2-litres and above controlled by CCL, this was a big blow even though one industry source maintained that it was more expensive to assemble locally then to import a complete car.

At this point, CCL was deriving at least half of its profits from its Malaysian Mercedes-Benz and Mitsubishi business; in Singapore, its commercial bus business was driven by the growth of the country’s bus services that had over 1,000 Mercedes-Benz busses operated by the Singapore Bus Service. CCL immediately moved to diversify its business interests. Ford closed its Bukit Timah plant in June 1980, and CCL shut down its Hillview Avenue plant in July. The Company reappraised its business and identified the engineering and property sectors as its “legs” for the new decade.

The Company’s flagship office on Orchard Road/Penang Road had come under the spotlight in late 1978 when the government served CCL notice that its land would in due course be acquired for redevelopment to “strengthen tourist facilities along Orchard Road.” By 1985, CCL relocated its corporate headquarters to two floors in Liat Towers at the other end of Orchard Road. Liat Towers, named after Chua Cheng Liat, was developed by the Company in 1965, but was sold in 1975.

Despite these challenging times, CCL experienced five years of steady growth and distributed healthy dividend payments between the Company’s jubilee year in 1974 and its 80th anniversary in 1979.

1980s – BARBARIANS AT THE GATE

1980s – BARBARIANS AT THE GATE: In early 1980, Singapore imposed further short-term measures to curtail vehicle growth with tax increases to “discourage any net increase in the number of cars registered”. In 1985, Malaysia’s National Car Project came into fruition and the first Made-In-Malaysia car, the Proton Saga (where Mitsubishi provided engine technology) rolled off the factory. Malaysia’s New Economic Policy (NEP) of wealth restructuring mandated that Malay participation in companies in Malaysia had to be at least 30% in shareholding by 1990. This presented some complex issues for CCL and CCB’s boards.

Against this backdrop, in March 1983, CCL’s share on the Singapore Stock Exchange saw a sharp increase in volume traded. Speculation was rife that Malaysian conglomerate Malayan United Industries (MUI) had amassed the Company’s shares and was interested in a takeover using its listed associate company Pan Malaysian Cement Works (PMCW) as its vehicle. CCL was a solid investment with stock price trading at parity to net asset value at the time. There was also talk that unlisted Pontiac Land, owned by Indonesian property developer Henry Kwee who held a 5.6% stake in CCL (CCL held a 20% stake in Pontiac Land’s Intercontinental Pavilion Hotel in Singapore), would make a counter offer in support of the existing board.

True to speculation, PMCW announced in March 1983 that it had accumulated a 10% share in CCL. CCL’s share price rocketed to S$5 (from around $3 in October 1982). The press also reported rumours that some members of the Chua family had been disposing of their stock. The scramble for CCL shares had barely begun.

By June 1983, as part of its major diversification program, Malaysian-listed General Corporation Bhd had amassed, through its subsidiary Malaysia British Assurance Sdn Bhd (MBA), a 10% stake in CCL’s Malaysian associate company CCB; it was deemed a passive investment. Later, in November that year, the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO) announced that it had accumulated a 5.4% stake in CCL (KIO also had a substantial stake in Daimler AG). By January 1984, KIO had increased its share in CCL to 10%.

In the meantime, Daimler had been giving its own distribution and dealer networks a close look. With the improving European and American economies of the 1980s, the German manufacturer had set a goal of increasing its passenger car sales by 10% to 600,000 in 1986. It was also intent on maintaining its leading position in the heavy commercial vehicle business. Its relationship with CCL’s board was a close one, and Daimler viewed Singapore favourably as its “turning table in South East Asia”. Even so, there was talk that Daimler was encouraging CCL to grow the commercial vehicle business. The Company was already focused on growing its non-vehicle operations in the long term.

WHITHER THE WHITE KNIGHT?

WHITHER THE WHITE KNIGHT?: In Singapore, Chairman Chua Boon Peng’s directorship in distressed packaging company Lamipak Industries was starting to raise concerns. Lamipak’s financial troubles reported in the press appeared to have been festering well before 1985, which may in some way explain why the senior Chua sold some of his stock in CCL to KIO in July 1985. A winding-up petition against Lamipak in October 1985 predated the collapse of marine salvaging, hotel, and property company Pan-Electric Industries in November 1985 which itself led to a meltdown of the Singapore stock market. Malaysian entities were already the largest institutional shareholders of CCL stock well before any of these developments had taken place. The local media spent an inordinate amount of time dwelling on the issue of who actually held the franchise for Mercedes-Benz – the Chua family or the listed entity.

Chua Boon Peng’s exposure in the failed packaging company meant he had to relinquish his board duties in CCL and CCB. The family’s minority interest in CCL was no longer a barrier for would-be suitors. With Malaysian government institutions already holding over 26% of the Company’s stock, and KIO an additional 19%, all that was necessary was to convene an Extraordinary General Meeting to seize control of a company that had the ideal distribution platform to tie in with Malaysia’s national car project. In September 1985, Tan Sri Datuk Haji Basir bin Ismail, Chairman of Malaysia’s Bank Bumiputra, was installed as CCL’s Chairman at an EGM.

CCL’s results in 1985 was the worst since its listing in 1969. In May 1986, the stock hit an historic low of S$0.96. Staff were laid off and showrooms were closed down. The passenger car market was down 49% in Singapore and 37% in Malaysia on a year-on-year basis. Basir insisted on systematic changes at every level of management. Of the original board of directors, the only family member that remained was Thomas Chua Boon Lee, the youngest son of Chua Cheng Liat, who was appointed Group Chief Executive in July 1986. The Company began a slow transformation, and extended its reach further into Malaysia.

MALAYSIA’S POLITICAL CLUB

MALAYSIA’S POLITICAL CLUB: The late 1980s and a large part of the 1990s saw CCL under, what was loosely termed, ‘Malaysian control’. CCL was now linked with the political elite of Malaysia. Corporate activity began to build again in 1989 when Yung Pui Company, a Hong Kong-based corporation with strong links to Malaysian corporate player Wan Azmi bin Wan Hamzah and Singapore property magnate Ong Beng Seng, emerged with a 15.1% stake in the Company. CCL expanded its Malaysian businesses thereafter. It acquired food retailer and distributor Cold Storage Bhd, and the Kuala Lumpur Merlin Hotel from a shaky Faber Group that was itself politically well-connected. The Malaysian connection was also paying off in Singapore; CCL was appointed sole distributor for the Proton Saga in Singapore.

Yung Pui subsequently unwound its stake in CCL and sold it to Edaran Otomobil Nasional (EON), the sole distributor of the Proton Saga in Malaysia at the time. In 1992, CCL, in conjunction with Ong Beng Seng’s company Hotel Properties Ltd, took over Singapore-listed property company Malayan Credit Ltd (MCL). There was yet no clear strategy for CCL. It made analysts wonder if the Company had lost direction while the strength of the Mercedes-Benz name allowed the motor business to run on autopilot.

In December 1992, the market was taken by surprise when the investment arm of multinational conglomerate Jardine Matheson Group, Jardine Strategic Holdings (JSH), bought over KIO’s 15.93% stake in CCL for S$212 million. By then, CCL had a market capitalisation of S$1.2 billion with three core businesses – vehicle sales, properties, food and retail. Ahead of Hong Kong’s handover to China in 1997, Hong Kong corporations were actively looking to diversify and expand their business opportunities beyond their borders. CCL, no longer under any family control, was to become an excellent platform for diversification plans into ASEAN.

Words by Eli Solomon

This article appeared in Rewind Magazine – Issue 007, July 2011. Content obtained with the help of the late Chau Boon Unn, the late Eric L.S. Jennings1 and Rebecca Solomon.

References

Jennings, Eric L.S. Wheels of Progress – Seventy-five years of Cycle & Carriage. Meridian (1975).

Footnotes

- Eric Lancelot Stuart Jennings [b. 23 July 1912, Ipoh – d. 1997] arrived in Ipoh, Malaysia in September 1931 to join his father J.A.S. Jennings, OBE (54, b. 1 December 1886, Singapore – d. December 1936, Batu Gajah Hospital, Ipoh) as Assistant Editor of the Times of Malaya newspaper. John Arthur Stuart ‘Jack’ Jennings was Editor and Proprietor of the Times of Malaya (purchased by Straits Times Press, Ltd, circa 1936). Eric Jennings was educated at London University and studied Malay at the School of Oriental Studies. He was appointed to the Board of Directors of the newspaper. Jennings later joined the Straits Times in Singapore and in January 1973 was appointed to the board of Neilson McCarthy Asia in Singapore and Neilson McCarthy Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur. Eric Jennings had a son, John Charles Stuart Jennings (3 March 1953, Singapore –d. 2007), later to become the Public Relations consultant for Cycle & Carriage.

Did the completely knocked down kits come with painted shells and body panels or were they painted in Singapore?

Also did the engines and transmissions come pre-assembled or where they also built from kits and tested in Singapore?

Thanks for your questions. The Mercedes-Benz CKD kits required the assembly of the panels, welding, tacking, sealing etc. C&C’s Hillview plant had its own dip tank for plating and oven baking booth for priming and painting the cars following assembly. The engines/transmissions, from my earlier chats with the late Stephen Seow, Plant Manager of the Hillview assembly works, came pre-assembled in crates from West Germany. A locally assembled Mercedes (200, 230, 280S models in the early 1970s) had all the necessary items installed – air-con, radio, even rustproofing. Eli