Updated 1 November 2021

Sloshing fuel around his bucket seat turned his bottom a deep shade of purple but it still did not stop Rodney Seow from winning the Tunku Abdul Rahman Circuit Race in Petaling Jaya in 1965 while others faltered from the heat. I tell it as he lived it.

“If I had known better, I would have entered the Grand Prix…just for the heck of it,” Rodney Seow recalled his Grand Prix debut in one of the supporting motorcycle races during the 1952 Johore Grand Prix; he had not considered taking part in the main race at that time. Then a student at the Anglo Chinese School (ACS) in Singapore, the young teenager had already chalked up some racing experience on his motorbike, having entered the popular Lornie Mile sprints in Kuala Lumpur and other sprint and hill climbs in Penang where his banker father was stationed in the early 1950s.

The last local winner of the Singapore Grand Prix (1961-1973), Seow was an automotive engineer by profession. A private person by nature, my initial dogged efforts to chronicle the history of the Singapore Grand Prix held (Snakes & Devils, A History of the Singapore Grand Prix, Marshall Cavendish, 2008) were met with his firm rebuffs: “I’m too old. I can’t remember anything.”

His sharp mind was nonetheless already in overdrive as I sent my first salvo of questions to him. Once past that modest exterior, I discover a very warm and forgiving individual. He had always been famed for his one-liners and dry wit, “the Seow humour”, I was assured. After countless chats, companionable lunches and drives around the old Singapore, Johore and Petaling Jaya street circuits with him, I sort of figured I had a handle on a racing career that spanned 18 years, the golden age of motor racing in Singapore and Malaysia, little realising that I had barely scratching the surface. The subject had disappeared into obscurity and I was glad he agreed to feature in The Moving Visuals Co.’s documentary Singapore Racing Legend, which aired in 2008.

This Lunch With Champions was not done over a single sitting but over the course of eight years and over many visits to his and Stanley Leong’s homes and travels up to Kuala Lumpur to visit friends and fellow racers.

To understand how it all began for Rodney Seow, I had to gain an understanding of the climate for motor sports in the 1950s – not just on Singapore Island but throughout the Malaysian Peninsula and Hong Kong. Without a doubt, this was a prerequisite.

UNDERCOVER: More than any other sprint race, Seow fondly remembered the Rahang Road half-mile Seremban Sprint (first held in 1938) for being the most exciting club event during its time. The sprint attracted the best bikes and cars from as far as Penang and Singapore. “The Seremban Sprint was more popular with the racing crowd as a venue simply because this was the only other race outside of the Lornie Mile that we could participate in that was not too far a distance to travel. We were starving for racing!” he recounted with a grin, admitting to riding a borrowed motorcycle from a friend and not telling his parents about it.

Seow competed at the 1952 Johore Grand Prix on a Norton International 350 in one of the support races and it left an indelible mark on the young student. He took fourth place in class, having led the race at one point, but slid off on lap 7; he was hooked. I was shown photos, taken by a schoolmate of his. “I think I was the only student racing, quite a celebrity…I wasn’t interested in motorcars then,” he admitted. I wonder if Seow already smitten by the Malayan-built Specials and the Cooper JAPs of the era. His vivid recollection of the Silver Arrows cars gave me a better understanding of what enthusiasts such as Wong Loong Cheong had encountered in building his Silver Arrows (there were at least three!). That Seow recalled the awkward rear brake bias of the early Silver Arrow was typical of the man, he saw things as an engineer would.

GRADUATING TO FOUR WHEELS: Smitten by the racing bug in the early 1950s, Seow returned to Malaya in 1959 after a six-year sojourn studying in the United Kingdom. He found a whole new crop of drivers with cars eager to get back into the sport after a hiatus of several years (there was no Grand Prix between 1954 and 1959): Johore would re-host the annual Grand Prix from 1960 and Singapore’s inaugural Grand Prix would follow suit a year later.

Seow remembers the gulf between those who had the money to buy the fast cars and those who did not and therefore had to conjure up creative modifications to stay competitive. For the latter group, “there was no access to performance equipment, let alone specialist-tuning magazines… each modification was experimental with whatever elements of logic only engineers comprehend,” he recounted.

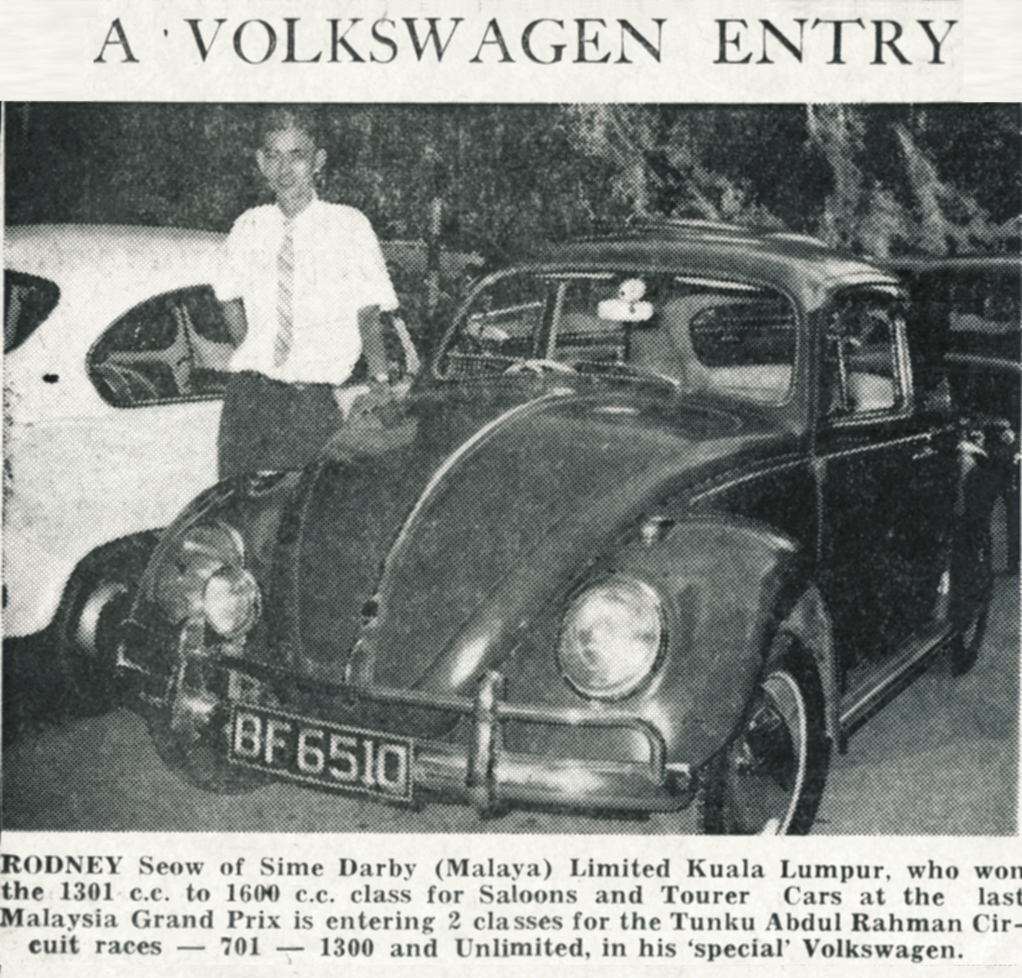

His first go on four wheels was in a Kuala Lumpur-registered VW Beetle. Not content with its paltry output, he invested in an Okrasa speed conversion, the installation of which he undertook at home. “The only one with the Okrasa-VW in Singapore and Malaysia,” he reminded me. The car, he sheepishly recalled, “was written-off one night on Jalan Duta in Kuala Lumpur by wrapping it round a lamppost before one of the Grand Prix.” In its place came a Volvo B18 Amazon, courtesy of good friend and another of Singapore’s all-time racing greats, Yong Nam Kee, “Fatso Yong” as he was fondly referred to. Yong had won the 1962 Grand Prix in Singapore in a Jaguar E-Type Roadster. Yong and Seow were all part of a close clique of local bike riders turned racers living in Singapore. The others in the clique include then school teacher Eric “Double-O” Ooi and the Chan brothers (Lye Choon and Lye Huat) of auto importers Eastern Auto. They hung out at the Eastern Auto showroom on Orchard Road while the more mature racers gathered at the Aioki Bar on Killiney Road.

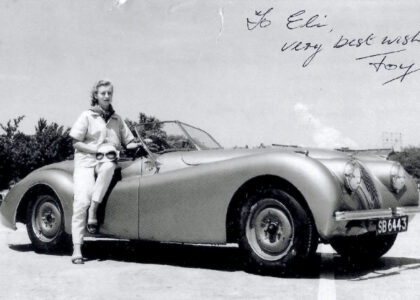

RODNEY AND THE FERRATUS : The natural progression from bike to tin top to sports car did not take long. With it came a long-lasting friendship with architect Stanley Leong. Leong had an eye for attractive sports cars and he too was into racing, having won his sports car class at the 1957 Changi Circuit Races in his MGA[LANDING AT CHANGI in 1957]. Mindful that the Lotus Elevens and Lola Mk1s were dominating the local club races, Leong chose to abandon his S.L. Ferrari (an MGA-chassis Ferrari Testa Rossa lookalike body) in favour of an early Lotus 15 [chassis 605] from the United Kingdom. Onto the MGA chassis went his 2-litre 4-cylinder Ferrari Mondial engine obtained on his honeymoon in Hong Kong] which had come from the da Costa-Baker Macau Grand Prix car. Mated to it was his MGA gearbox. Seow would soon have a fleeting association with the ‘Ferratus’, the name the Lotus-Ferrari would ultimately become known by.

“I didn’t know him that well at that time,” related StanleyLeong. “One day he came up to my office just before 9 or 10am and said ‘Eh Stanley, you want to sell your car?’ I said, ‘Which car? Oh, the Lotus-Ferrari. And you want it?’ I told him, ‘You know the history, right? You know it cannot finish, right?’ ‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘I’m an engineer, I know how to do it.’ Ok just shake my hand, sign here Okay…Take the car away.” The Ferratus, along with its handling and overheating issues, had found a new home.

In 1963, the blue Ferratus could do no better in Seow’s hands. “He ran with this car for a quarter-lap in the Johore Grand Prix…He started, he took the lead, came to Zoo Corner, he couldn’t make it…the engine just went Brrrrr, Brrrrr…He went straight to Kuala Lumpur, and that’s the end of the car, no more,” Leong laughed when he recollected the story over a glass of wine and a cigar. “And after that we joined forces together,” he told me. Seow remembered that Leong was “pissed off. End of [the Ferratus] story.”

Seow had found a new friend and a backer in Leong and the combination proved a tour de force in South East Asia, but not before a major setback that threatened to derail local motor sports.

LOSING A FRIEND: The 1963 Johore Grand Prix will always be remembered for the very unfortunate accident that took the life of one of Singapore best-loved racers, Yong Nam Kee. Speculation raged over the possible causes of the crash on the 58th lap when Yong, in a Jaguar D-Type, was just 30 seconds behind leader and eventual winner Albert Poon in a Lotus 23. Seow remembers that “the D-Type was no match for the Lotus 23 – which had a smaller [and much lighter] motor, was a lighter car, stopped quicker, accelerated quicker.” Yong’s death resulted in an outpouring of grief in the local media.

Shortly after, Seow and Leong, along with others, announced their retirement from the sport, although both eventually reversed their decisions. Leong had himself suffered a setback during the ill-fated weekend. His Merlyn Mk6 Sports Car, the same shade of yellow as the D-Type, had caught fire and burnt to ashes during Friday practice. The duo persevered and a new strategy was formulated for the 1964 race season.

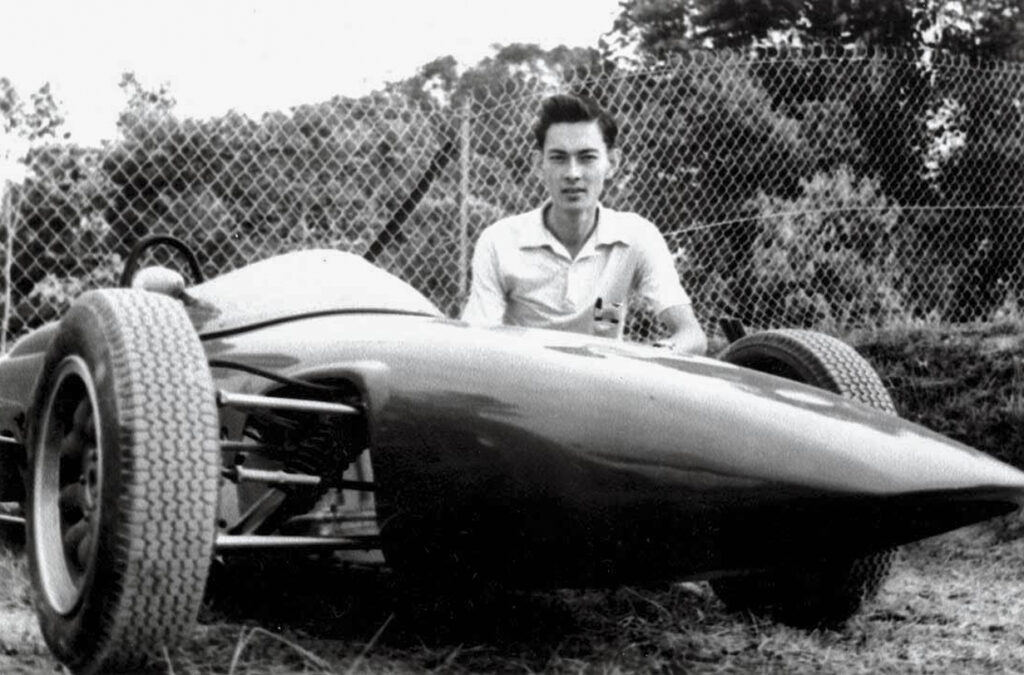

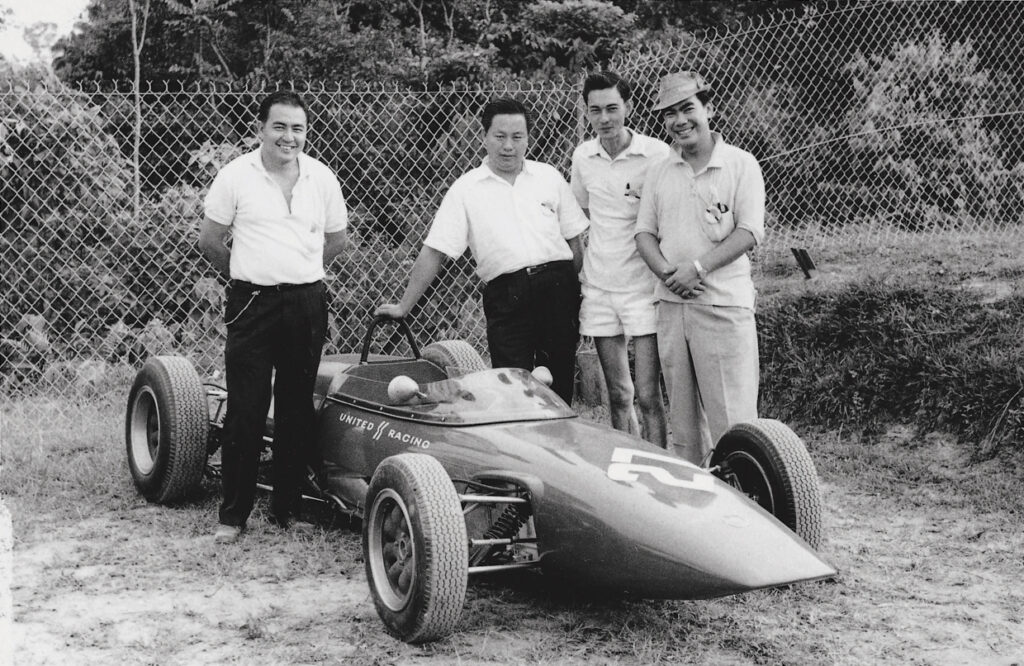

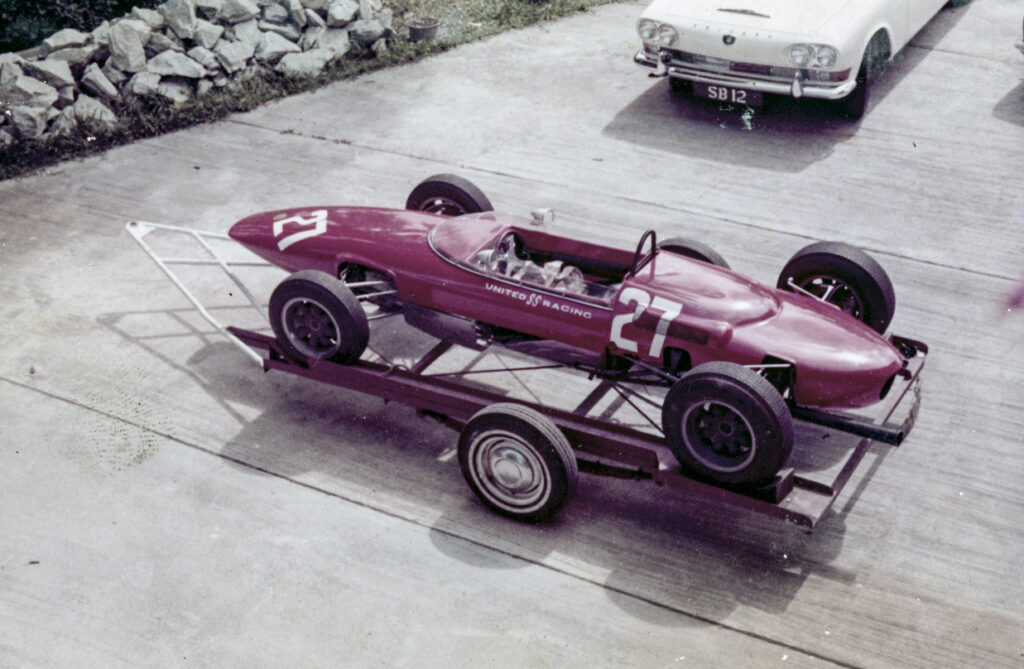

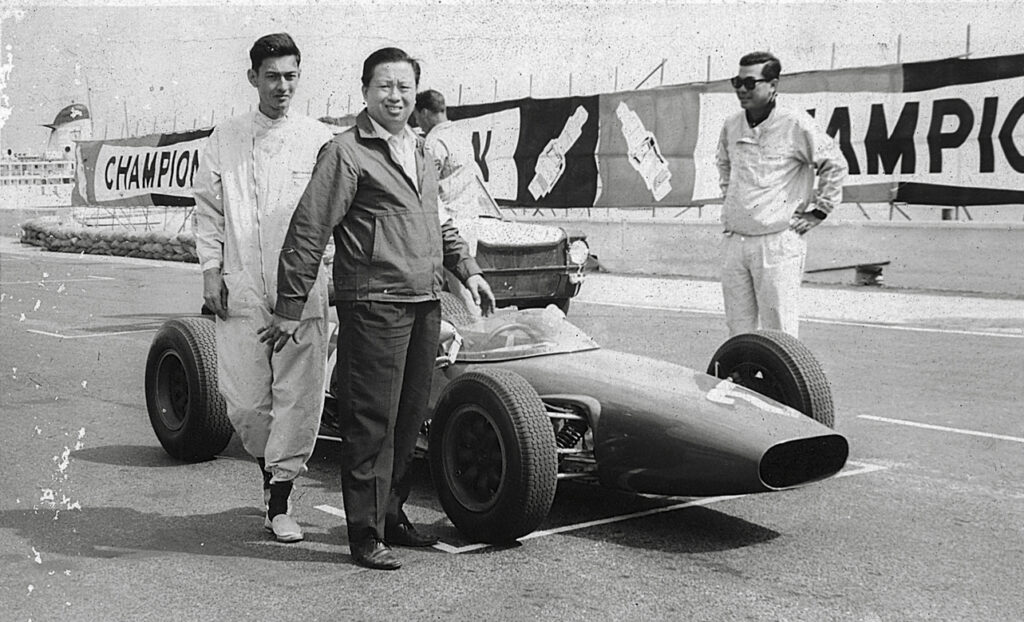

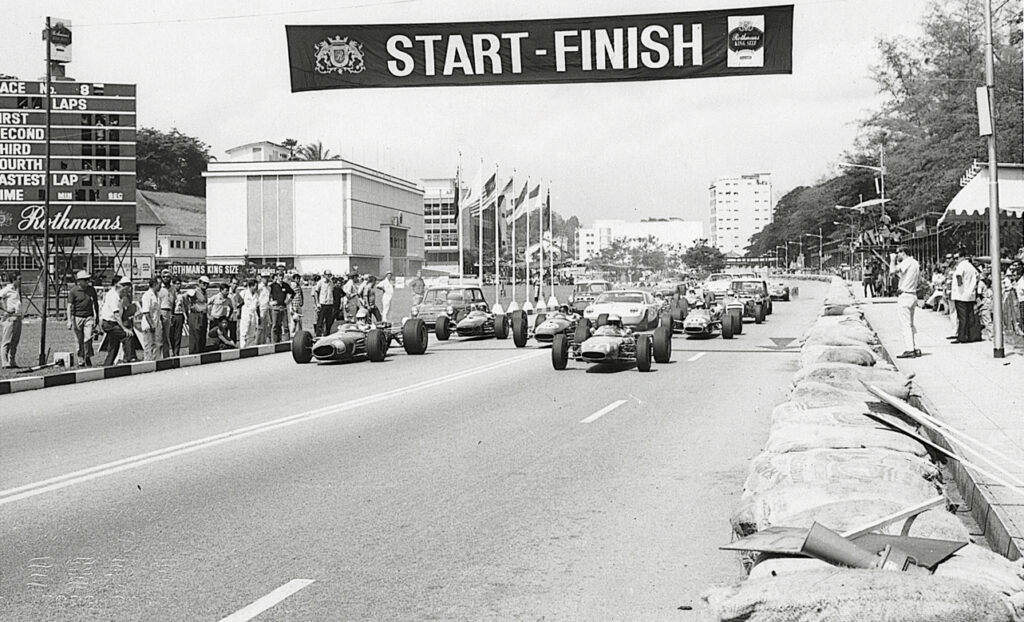

NEW ROADS: The purpose-built rear engine single-seater had come to South East Asia in 1963, but it was not till the following year that two very competitive local individuals had the necessary cars to compete equally in the gruelling 60-lap (about 291km) Singapore Grand Prix. Leong and Seow’s new équipe, United SS Racing, imported an ex-Works Merlyn Mk5 car (sold to them as a Mk7) while Lee Han Seng returned from studies in the United Kingdom with a Lotus 22.

Without a permanent circuit on the island, Seow, who took his racing seriously, faced the problem of not being able to practise with his new car. The Jurong industrial township was under construction and miles of fresh tarmac was being laid down. Seow and fellow enthusiast Mike Cook “would tow [their] cars there and tune them.” For a short while, Jurong Town, otherwise known as ‘Goh’s Folly’ (after Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s Minister for Finance at the time and the architect of the project) had become Seow’s proving ground.

MAGIC MERLYN 1: While the enthusiasts and corporations mulled over the idea of a permanent circuit in Selangor, a temporary location was found for the 1964 Tunku Abdul Rahman Circuit Race at a factory estate in Petaling Jaya. Seow qualified his Mk5/7 at the front of the grid, alongside Lee Han Seng and Steve Holland from Hong Kong. He led the race for the Rothmans Challenge trophy in wet conditions for 26 out of the 50 laps until disaster struck…yet again. Two of the spark plugs burnt out, one after the other. His misfortune was someone else’s gain.

Of the temporary street circuit he recalled: “It was very dangerous to drive…so bumpy and at the bends, especially at the Rothmans Corner, my car was pushed about.” The Merlyn Mk5/7 nonetheless posted Fasted Time of Day that wet afternoon.

His first Grand Prix win would come a year later in Malaysia in 1965 at yet another temporary circuit, this time in Petaling Jaya. “This is when I burnt my backside,” he mused as he recalled the sloshing of fuel around his bucket seat. It was a tortuous race for all the drivers. “Yes, yes, Han Seng’s Lotus 22 against the Merlyn 7…Han Seng collapsed, heat exhaustion. Alan Bond, heat exhaustion. Me? I stayed on the course with a burnt backside…I figured out I was ahead, we were swapping leads. I was going to give up. I said, no, if I pull in, my backside will still be painful. So what the hell, might as well stay on the track. My backside was purple for about six months.”

Seow understood the perils of the sport and these long distance races bothered the engineer. “Oh these long range fuel tanks…they are hazardous, you’ve got one under the seat, two on the side, one on top by the dash.” The cars were moving fuel tankers!

Seow’s margin of victory over John Tse’s second-placed Elva Mk7 Climax was a massive two laps. The little Elva Mk7 FWA Climax from Hong Kong was such a sweet-handling car, Seow and Leong immediately negotiated to buy it from Tse for S$6,000 – straight after the race! The car was “in tatters, under-body was torn away, no firewall protection in the front,” Seow recounted, so he immediately had the car delivered to the Singapore Motors’ workshop off Somerset Road where he was now working.

“We used to drive it around town during the weekends with trade plates. Once, the [Hewland] Mk4 gearbox seized just outside Gleneagles Hospital so we changed it to a Hewland Mk8,” he recalled. Nonetheless, the 1147cc Climax FWA motor was for Seow “a very sweet engine, able to idle at 450 rpm.” But of course once the Twin-Cam Lotus 23Bs made their appearances, no matter how hard they drove the little Climax, the 23Bs would always have the power advantage. “That’s when Stanley got angry and brought in the [Elva] 7S with the Nerus BMW engine.”

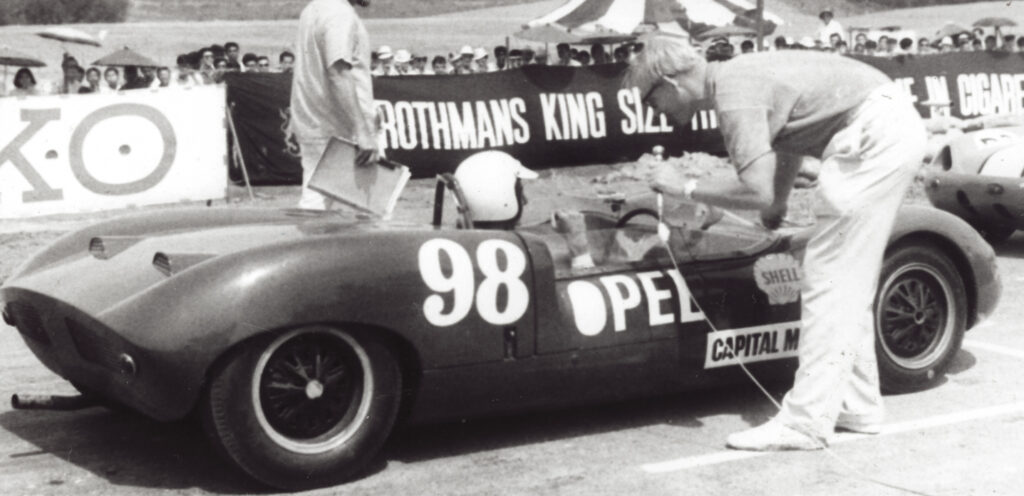

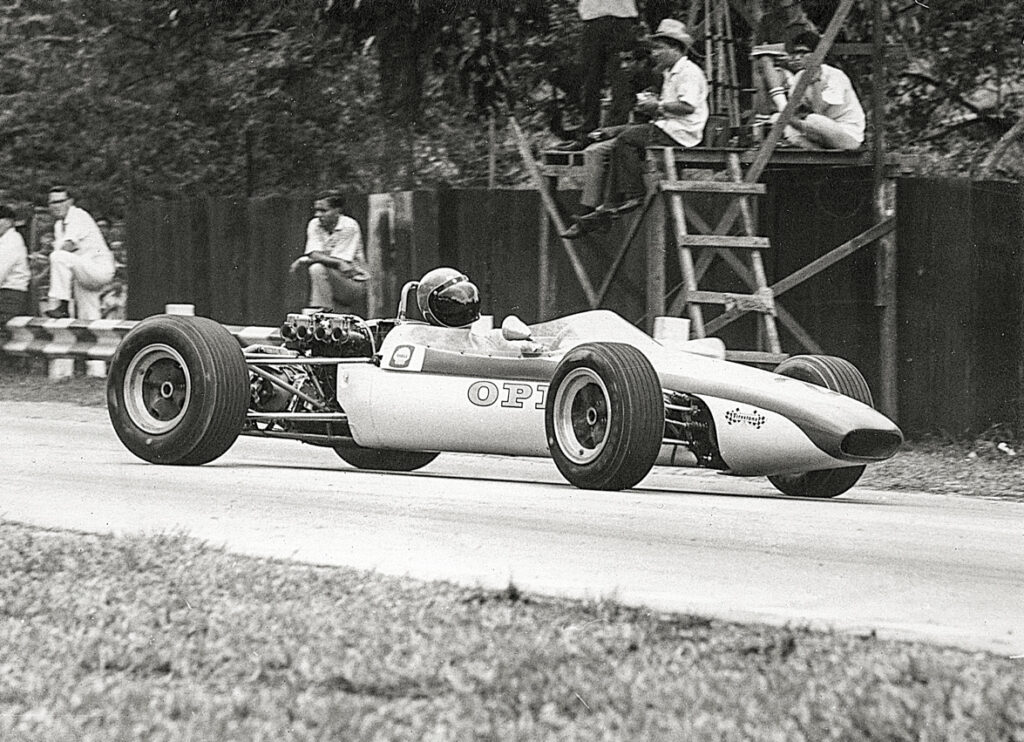

GROWING PAINS: By this time, Seow and Leong had a good working relationship. Their connection with Singapore Motors (Leong was a director of the company) enabled the pair to capitalise on the facilities and the Opel brand. Leong recalls one of the Opel engineers questioning Seow about an Opel Kadett he had been tinkering with for saloon car racing. “The engineer came and asked Rodney, ‘Please tell me what you have done to this thing.’ Rodney’s reply was, ‘Nothing, just lightened it, that’s all.’”

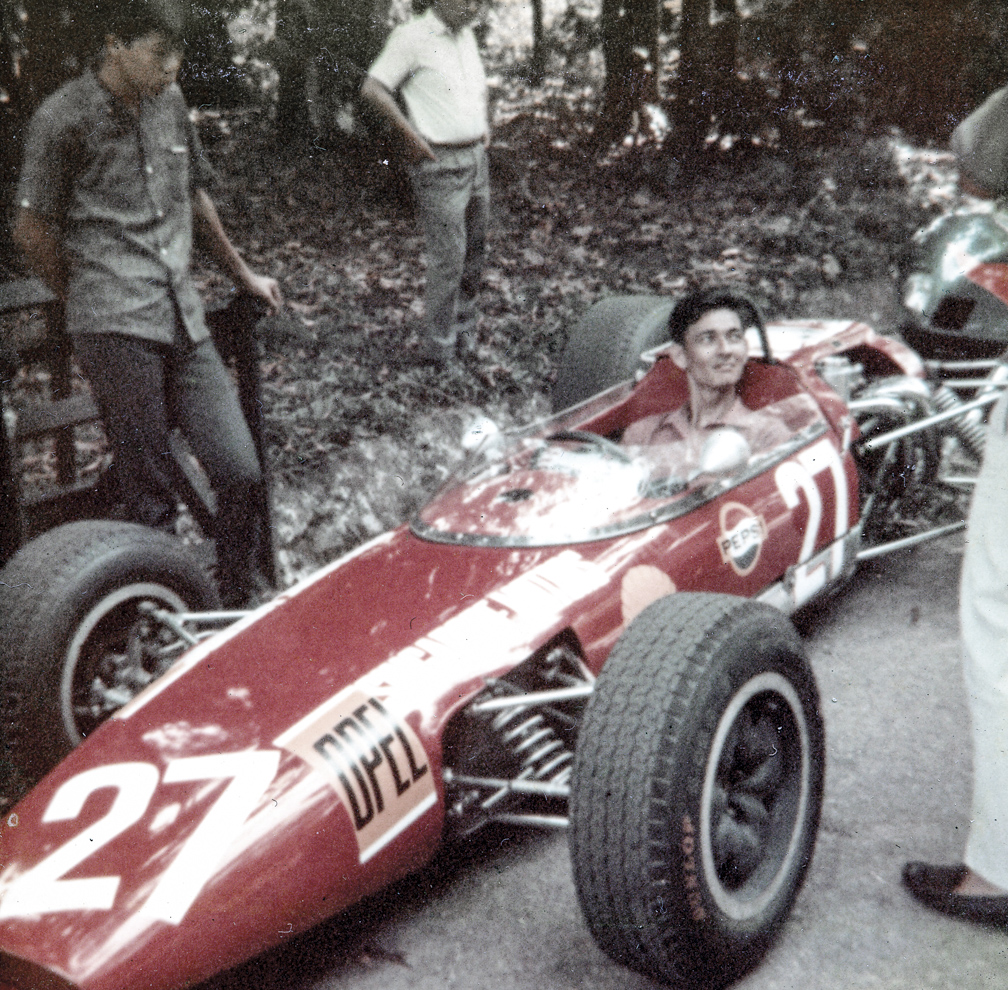

The Opel Kadett was being prepared for the Saloon and Tourers race for the upcoming 1964 Singapore Grand Prix with new close-ratio Ford gearbox, aluminium doors, bonnet and boot, and Perspex windscreens. The carburettors were replaced by a pair of Dell’Ortos; the engine had a Geo Wade camshaft; the pistons were custom-manufactured by Mahle; and of course, the engine had been balanced. Seow set a new 851-1000cc class lap record in the Grand Prix in the car. One may notice the Opel name on the single-seaters and even on Henky Iriawan’s car. Seow reminded me that there was not an iota of Opel or General Motors in any of those cars.

In 1966, Australian Greg Cusack was hot favourite to win Singapore’s first post-independence Grand Prix in his Brabham BT10. He was well ahead of the rest of the pack when he crashed at Devils. It seemed that Lee Han Seng and Seow would be in with a chance. By lap 15 however, a section of Seow’s exhaust header pipe fractured, causing the pipe to detach and fall off at The Snakes. He promptly stopped the car, “picked up the piping-hot piece using two roadside twigs, stuck it under the elastic straps holding the rear body cover and drove to the pits”…to drop off the offending part. The Merlyn, Seow recalled, was “noisy as hell and down on power.” It was necessary to stop, “because if I lose that part, I’ve got to make another one.” Lee Han Seng won his first Grand Prix but others saw that Seow was far more sympathetic to his race car. Seow’s advantage was that he did most of the spannering himself, until much later when he was assisted by aircraft engineer Loh Yap Ting.

The Merlyn Mk5/7 had served its purpose after their trip to Macau in 1966. “It broke up, it couldn’t take it, couldn’t take the pounding…kept hitting the bump stops,” Seow remembered of that weekend in Macau with Stanley Leong and Loh Yap Ting. He recalled the trio never visited the casinos in Macau but attended all of Teddy Yip’s wild parties. Following the Macau race in 1966, the Mk5/7 was replaced by another Merlyn, a Mk10 Twin-Cam Formula 2 car. Lee Han Seng had graduated to a newer car, a Brabham BT18 BRM, while Hong Kong’s Albert Poon had moved on from his obsolete Lotus 23B sports car to a single-seater Brabham BT21. 1967 however, would be Rodney Seow’s year.

MAGIC MERLYN 2: Winning the 1967 Singapore Grand Prix with the Merlyn Mk10 meant little to Seow until well after the celebrations ended that Easter. He remembers the weekend not for the magnificent win but for how tiring it was for him. “I did not get much sleep as the mechanics and I were in the garage up to 4am preparing the Merlyn Mk10, the two Elvas and Dodjie’s [Filipino Arsenio Laurel] Lotus 41.” Compared to the Mk5/7 Formula Junior, the Mk10 was far stronger on all counts. Seow’s win would also be the Colchester firm’s only international success with the Mk10 model.

Seow topped off his very popular win in Singapore with another in the very first race at the new permanent circuit of Batu Tiga that same year. At a little over 100lb, he was light but no lightweight on the circuits. Singapore now boasted two champion drivers.

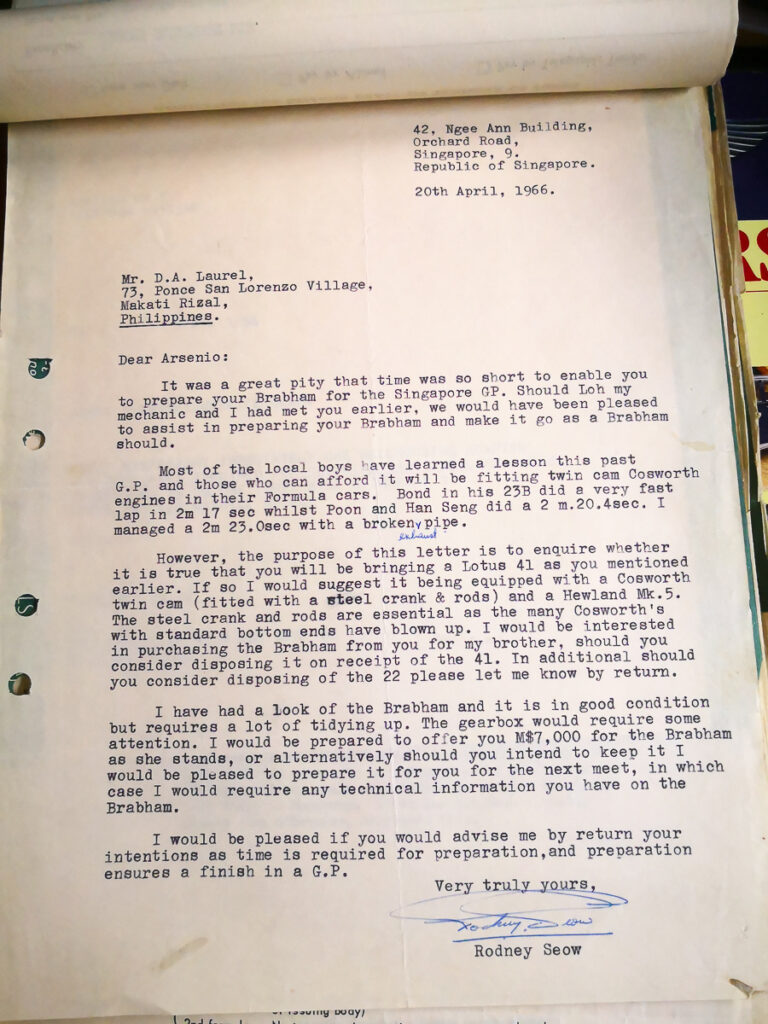

TO FINISH FIRST, FIRST YOU MUST FINISH: Lee Han Seng’s withdrawal on the eve of the 1968 Singapore Grand Prix was the shock of the year for the racing community. Upset at how the local Grand Prix had polarized competitors because foreign drivers were receiving considerable financial support from the local organisers while the locals were left to fend for themselves, he took a stand and did not enter the event. Seow was facing a different dilemma. Competition was fierce, the cars were much faster than ever before. His latest mule, the ex-Mike Knight 1964 Japan Grand Prix-winning BT9 Brabham chassis F3.3.64 , had been sidelined, the car having failed him at Batu Tiga earlier in 1968. Interestingly, Seow already had an interest in Dodjie Laurel’s BT9 and actually made the Filipino an offer of M$7,000 for the car as it stood following the 1966 Singapore Grand Prix.

It was back to his Merlyn Mk10 with a new S$10,000 Martin engine. Sadly the complex Martin engine was a “dud”, he lamented. Fortunately the Twin Cam Brabham, now sporting revised suspension, new BT23 nose-cone and candy-apple red paint, was race-ready and quickly mobilised after practice. There had been some serious upgrades to the ex-Mike Knight car that had won the Suzuka International Grand Prix in 1964 – in fact, it looked nothing like the car Knight and Dodjie Laurel had raced. In the 1968 Singapore Grand Prix Seow was up to third at one point before attempting to lap back marker Chong Boon Seng (in a Lotus 41) on the inside line through Devils Bend. The cars touched and a furious Seow ambled back to the pits to try to have the damage repaired. It was to no avail.

The 1968 Johore Grand Prix, the last time a street race would be held in the state, would also be Seow’s last Grand Prix. Some of the cars at the front of the grid included Seow’s Merlyn Mk10, a Mildren-Brabham Intercontinental Climax 2.5, a Brabham BT14/15/16, a Brabham BT21-Alfa and an Elfin 600 – Garrie Cooper’s winning car in the 1968 Singapore Grand Prix held earlier in the year. A torrential downpour had caused havoc during the race that was red-flagged when the casualty list became unbearable, leaving the win to an outsider driving a Lotus Super 7.

In practice though, Seow matched one of Australia’s top racers, the ‘Jolly Green Giant’ Max Stewart, “even with unchanged gear ratios from Batu Tiga earlier,” he enthused. “This pissed him off and caused him to overdo it and he overshot a corner,” Seow recalled with some satisfaction. He was to encounter problems himself as the street circuit was fast becoming a skating rink. “I think I was leading. I lifted off the throttle too quickly before Zoo corner and the car aquaplaned…did two or three spins on the road. I picked up the bodywork and placed it upright against a tree on the seafront, looked down the road and watched Alan Bond’s Porsche 911S, a gaggle of Minis and Henky’s [Iriawan] Elfin 600 Prototype proceed to spin off the track as well…I heard someone say afterwards that my car went up a tree,” he chortled.

ASSEMBLING CARS: Racing has always coursed through Seow’s veins, but work commitments at Capital Motors’ assembly plant in Tampoi, Johore and a growing family gave him little time to focus on racing. 1969 would also see an influx of Australian and Kiwi professional drivers with considerable backing; it would have been extremely difficult to match the sort of support they received while holding down a full-time job. A Brabham BT23C (chassis number 1) and an Elfin 300S Sports Racer were acquired. With the right engine, either would have put Seow at the sharp end of the grid had he chosen to continue; work however took precedence. Leong, one of the office holders of Capital Motors, was the architect of the plant while Seow designed and installed the plant equipment and ran the business operations with 120 workers under him assembling Opel Kadetts and Rekords. They also did specialist conversions, including a RHD conversion of the Opel GT for Iriawan, a project that took Seow three months.

There was one other fleeting drive in competition and that was in an unfamiliar car – City Motors’ Alfa Romeo GTA at the Batu Tiga Grand Prix International MMSC Clubman races in October 1969. Seow was entered in the GTA and took it out for qualifying on the Saturday. He qualified the Alfa in second place with a lap time of 1:41.1, behind Harvey Yap and his 2-litre Datsun SSS (1:39.1). Unfortunately, Seow had to rush back to Singapore on business and so handed the Alfa to Saw Kim Thiat to race on Sunday.

Seow’s participation in the sport would continue indirectly for a few more years, assisting good friend Henky Iriawan in the early 1970s and following with vicarious interest regional race drivers such as the “naturally gifted” Sonny Rajah in the ex-Ronnie Peterson March 712M that he so admired. There was talk of a comeback in 1971 after Seow answered race car trader Bob Howlings advert for a Brabham rolling chassis BT23C/1, £850, the ex-Graham McRae car (run by Frank Williams). A Brian Hart twin cam motor arrived with the car. The engine was eventually sold to Jan Bussell, possibly for use in his McLaren M4C for the 1971 Macau Grand Prix (which Bussell won!). The rumour that a new team of ex Singapore champions were entering a Brabham BT23C, a Brabham FVA and an Elfin 300 spread ahead of the 1971 Selangor Grand Prix in September but nothing came of it although correspondence between Seow and Motor Racing Development’s Alain Fenn suggested otherwise – certainly with respect with the purchase of BT23C parts (and BT35 front and rear wings). He never stopped following the sport and often attended the Malaysian races to watch his friends race. The cars and parts remained in his backyard for years, the BT23C finally advertised for sale in Singapore in November 1981. The Elfin 300, Brabham BT9, BT23C, Elva Mk7 and Elva M7S still exist but what of the Merlyn Mk5/7 and Mk10? That’s for a feature on the Magic Merlyns.

Rodney Seow was an excellent resource when it came to Asia’s motor sport history but one thing was for sure, if you ever talked to him about racing, you had better “know your arse from your elbow.”

RIP Rodney Seow (1935 – 9 August 2020).

This Lunch With Champions feature first appeared in Rewind Magazine issue 006, April 2011.