By Eli Solomon – interview with Louie Camus in 2013.

This article first appeared in Rewind Magazine 015, July 2013

If skydiving doesn’t work for you, there’s always motor racing, as the engaging Filipino Louie Camus discovered.

If skydiving doesn’t work for you, there’s always motor racing, as the engaging Filipino Louie Camus discovered.

This article first appeared in Rewind Magazine 015, July 2013

If skydiving doesn’t work for you, there’s always motor racing, as the engaging Filipino Louie Camus discovered.

“Who built the body for your racing Celica?” I asked the spritely gentleman as we sat outside his patio in Manila one cool morning.

“I did. I moulded the Celica. I had a whole shell of a Celica,” came the steady response, a ready smile revealing the easy-going demeanour of this wily competitor.

“When did you first start racing?” I asked the 78-year-old. The floodgates opened and Louie Camus’ weighty tome of a photo album quickly made its appearance.

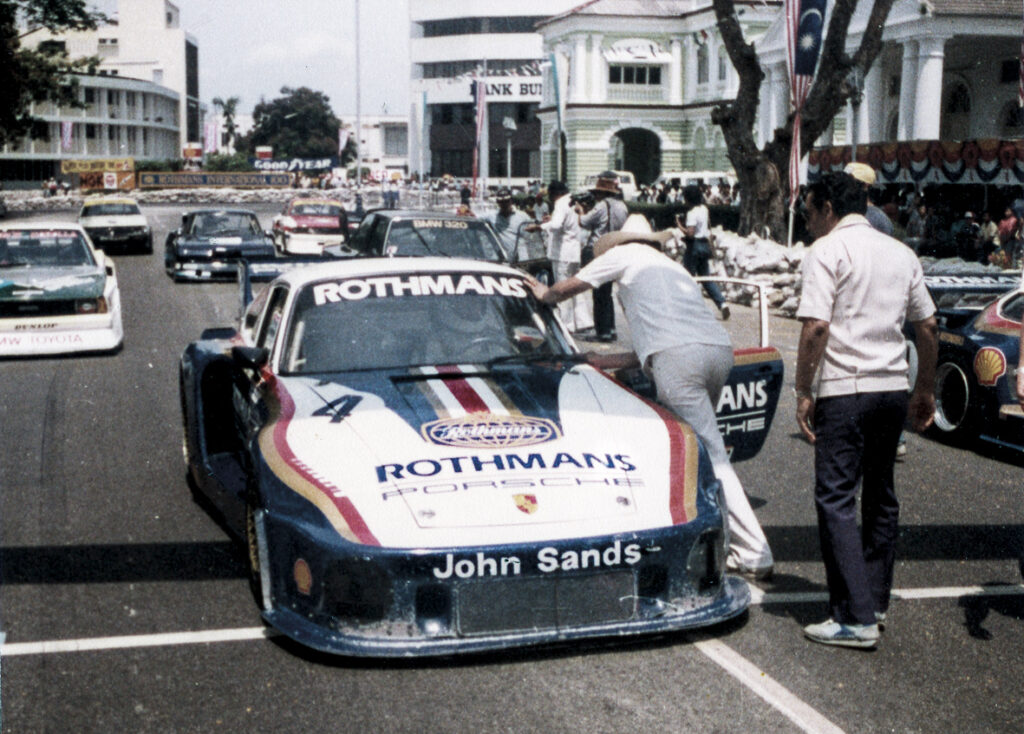

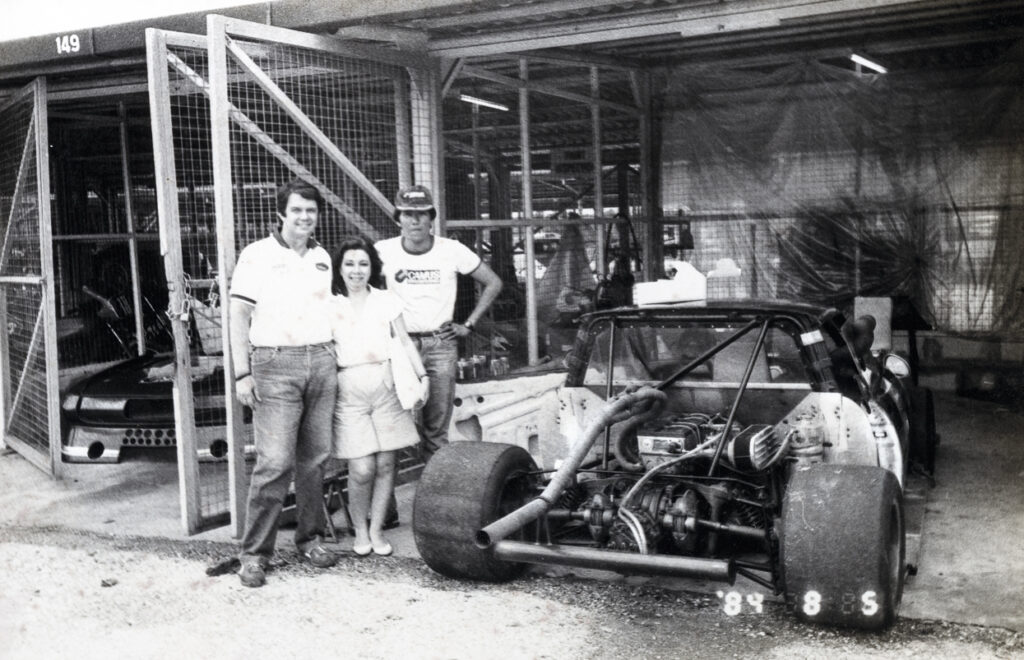

Louie Camus and his No.16 Celica-BDA faced a formidable grid of Super Saloons in the 1984 Malaysian Grand Prix, including the works Toyota Levin driven by Kiyoshi Misaki and Dick Ward’s Mazda RX7. The race was won by Ian Gray in the No.9 BMW 320i Turbo while Louie finished third.

LANDING ON THE RIGHT SIDE

“Well, it’s like this, my first hobby was skydiving. But I had an unfortunate accident. My main pack didn’t open, so I had to open my reserve parachute. Surface winds were strong. I landed on my side and fractured my left shoulder. They had to operate. That accident was in 1965,” he informs me with a grin.

“What do I do now? I can’t lift my hand high. That’s when I went into racing. Racing here would be slaloms, gymkhanas, and rallying, which I also joined,” he continues. The words flow with excitement as he recounts more stories.

Junep Ocampo’s definitive book, Fast Lane, covers a great deal of the Philippine motor sport history. It is in fact the only printed comprehensive reference on the subject. Listening to Louie’s accounts, however, delivered with a glint in his eye, beats reading any book.

Once very active in rallying, he tells me why he stopped. “We were going north once. They were building the Pan-Philippine Highway. They were building culverts along the highway which created big humps. We were going 160km/h and we would go airborne. In one of those humps, airborne, I see an old woman crossing. What do you do? Brake? Turn the car? You’re in the air. So I blew the horn. The old lady actually ran. I missed her by the skin of my teeth. From that time on, I quit rallying and only raced under controlled conditions.”

THE BUG BITES

“My first circuit race was in the Philippines,” Louie relates. “My first, what I would call ‘formal race’, was at the Cebu Grand Prix in 1969. I didn’t even complete the first lap. Over eager, crowded first corner, I spun out in a 1967 Toyota Corolla. I was working at Delta Motors [the Toyota distributors in the Philippines].” Nonetheless, the bug had bitten hard.

It was typical of Pocholo to counsel the young racer: ™This arm, all you have to do is lift it to the steering wheel, and that’s it.

“The second race…they had introduced the Toyota 800, the two-door coupe. [Ricardo] Silverio was the big boss, the president of Toyota distributor Delta Motors. He saw me tinkering with the car one day and asked what I was up to. I told him I planned to race the car. ‘That’s not the way to do it,’ he shouted at me. ‘You bring in a mechanic from Tokyo and do it right. I’ll fix it.’ The next couple of days, a mechanic showed up from Japan with a box of bits and proceeded to convert my car into a full race car.” The little 800cc machine was entered for the Greenhills Grand Prix and Louie surprised everyone by beating the larger Corollas. That propelled the young man to double up on his efforts.

ENTER POCH

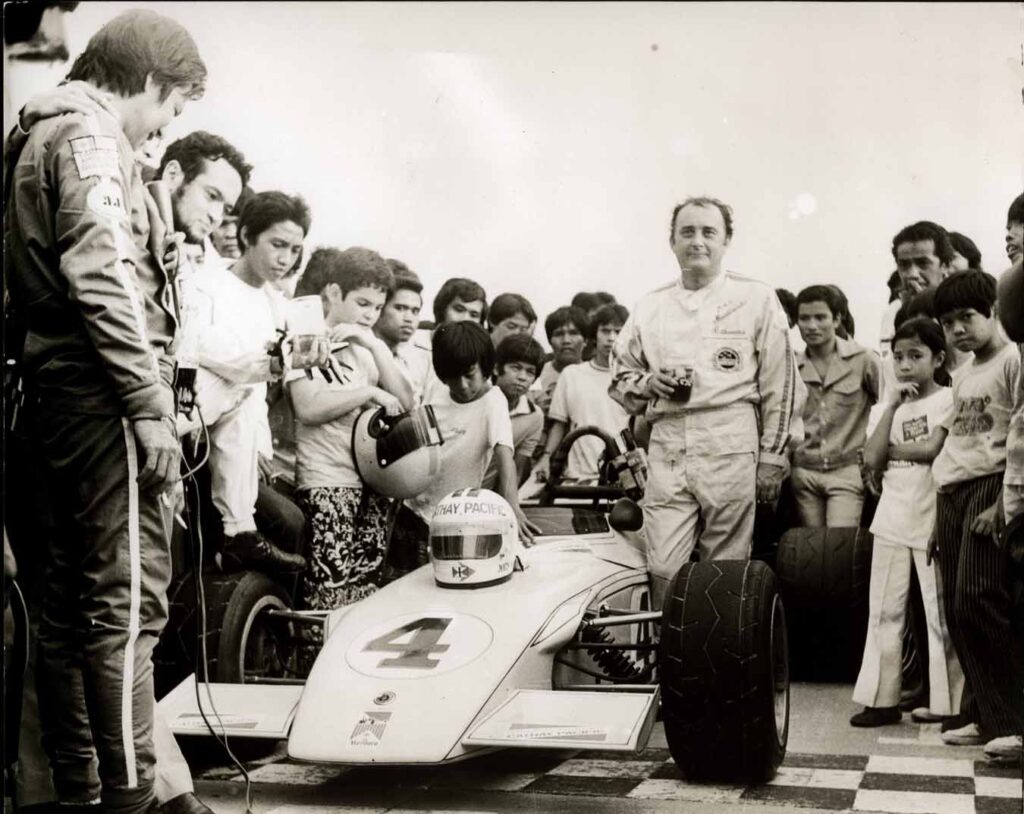

“The guy who influenced me a lot in racing was Pocholo,” he tells me after a short pause. Jose “Pocholo” Ramirez is one of the greatest names in Philippine motor racing annals, well known throughout Asian racing circles during the ‘70s and ‘80s in single-seaters, saloons and rallying. A television personality later in life, Poch, as he was affectionately known, created a racing dynasty that continues today.

Louie recalls his encounter with Pocholo with great fondness. “He was racing already when I was concentrating on my skydiving, so we would hardly meet. But after my accident, I would watch him race. He encouraged me.” Of his hampered arm, it was typical of Pocholo to counsel the young racer: “This arm, all you have to do is lift it to the steering wheel, and that’s it.” The racing legend, says Louie, “would race any time and any place.”

“Pocholo was lucky because Dante supported him. He didn’t even know what a distributor looked like, but he was a good driver. The moment we started talking about mechanicals, I would say, ‘Poch, you keep quiet,’” Louie recounts of their time racing at Shah Alam and Penang together.

RACING ABROAD

The 1970s were a challenging period for Filipino motor sport enthusiasts. President Ferdinand Marcos had declared martial law in the country from 1972 (which was finally rescinded in 1981) in an attempt to suppress increasing civil strife and the threat of communist takeover in the country. “After one or two years, Marcos prohibited rallying and motor sports, trying to preserve fuel as much as possible. It put the sport in a dormant state,” remembers Louie. Some local racers ventured overseas.

“What do I do? I first started to watch races in Malaysia and Macau, watching Pocholo race in the early 1970s. I decided I was going to start racing Formula Atlantics.” While single-seater racing was all the rage from the late 1960s, it was only in 1971 that capacity and engine regulations came into play in South East Asia. By 1978, with Formula Atlantic racing very popular globally, the South East Asian circuits quickly adapted and introduced this form of single-seater racing. Top level Atlantic cars were expensive and difficult to maintain, but the Asian drivers were still having a blast racing with their Australian and Kiwi counterparts at races in Macau, Penang and Selangor.

Not content with a single race car, Louie bought three Formula Atlantics – two Chevrons and an older Elfin. The Chevrons were previously owned by fellow racer Eddie Marcello while the Elfin-Toyota came from Dante Silverio. The cars may not have been competitive against the newer Ralts and Marchs run by the likes of Graeme Lawrence, Ken Smith and Steve Millen, but the racing was fun, and it was a good way to spend a weekend with his kids away from work and home.

Louie Camus recuperating in the ex-Graeme Lawrence March 76B – Selangor Grand Prix, December 1982.

“I raced in Shah Alam, Penang, Pattaya [the Bira Circuit], Ancol. I never raced in Singapore. I watched a race there one year and then they banned motor racing in Singapore,” he recounts as he rattles off names of people in the region he was close to, like Allan Tan of Borneo Motors, Albert Anthony of Rothmans, and Shah Alam’s well-known Clerk of Course, Jeff Amin.

RACING TIN TOPS

Louie’s foray into single-seaters was short-lived. Saloons and tourers continued to appeal because there was more chance of racing to victory around the hot and dusty circuits of Asia. Toyota saloons were the cars of choice amongst the Filipino racers disinclined towards single-seaters, the Corolla Levin and Coke bottle-shaped TA21 Celica being extremely popular.

Louie describes one memorable incident with his Corolla in Malaysia. “I remember [Singapore-based competitor] Del Schlomer. That’s when I had the accident with the Corolla. I beat Del to the green flag and led the race. On the back straight, I looked in my mirror and there was this big Chevrolet Camaro coming at me. Here comes the first corner and I lock up my brakes and slide right off, like a dart into the window of a rag factory! Oh my God, that Camaro was something else. Its hood was as wide as my car!” The Schlomer Trans-Am Camaro was the biggest and most intimidating feature of racing in Penang and Selangor during the 1970s [in fact, there were two Camaros in the region at the time, the other belonging to Ian Grey].

NO PROBLEM

“I have a funny story about Macau,” Louie says to me. Even with the oil crisis and conflict in the Middle-East in the 1970s, racing in South East Asia continued to grow, with Singapore being the exception. Penang and Selangor had biannual circuit races, Macau had its Grand Prix and Guia touring car races, there were street Grand Prix races in the Philippines, and even Brunei got into the act. In Indonesia, the 4.7km Sirkuit Jaya Ancol was completed in 1971 to meet demands of the many Indonesian enthusiasts who had been racing abroad for so long. The man behind this is another motor racing legend of Asia, Tinton Soepraptoe.

“When I first raced in Malaysia, it was in the red Corolla Levin that Dante Silverio had Pocholo drive in Macau earlier. It was a good car. But you know the Corolla’s short wheelbase is a little hard to handle. I raced it at Shah Alam. Then there was a race in Indonesia. I shipped the car there for the race.”

Louie Camus’ Fiery Corolla at Shah Alam.

At Ancol, Louie met Soepraptoe. The dates are hazy, but by all accounts, it would have been at the 1976 Indonesian Grand Prix held three weeks before the Macau Grand Prix. When Louie inquired about shipping the car to Macau after the race, “No problem, No problem!” was the assurance he obtained from Soepraptoe. “No problem,” repeats Louie. “Here comes race weekend in Macau. Pocholo, me, Pocholo’s wife, my wife, they were good friends. We were all there. We arrived and I am looking for my car. Can’t find it.”

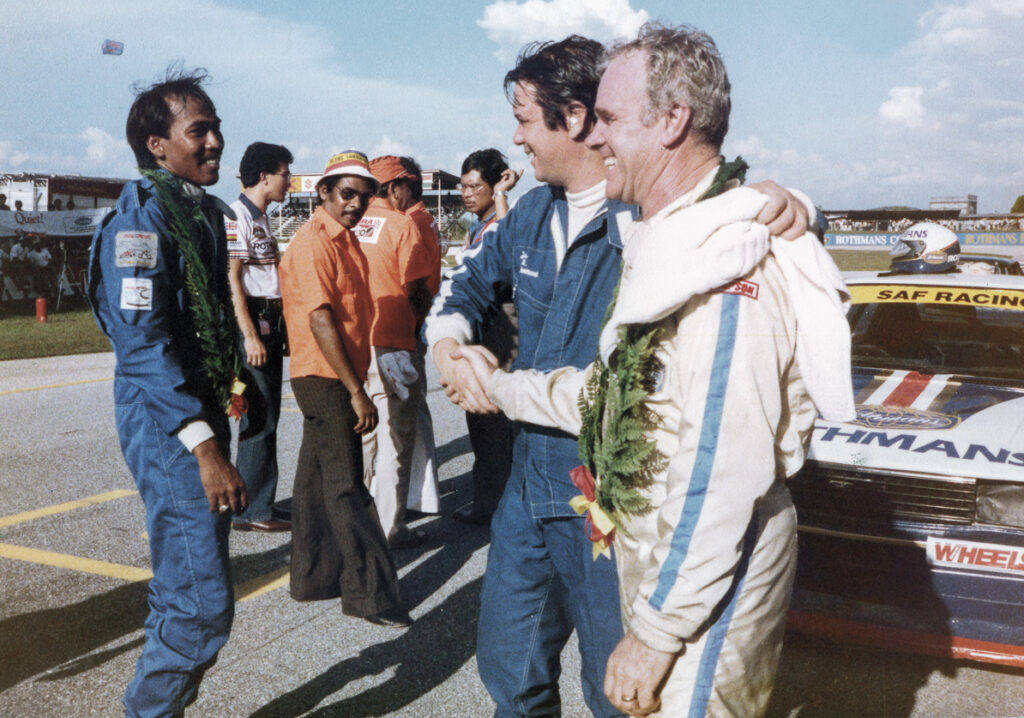

Louie Camus wins the 1984 Hengky Iriawan and Saksono Memorial Cup Race at the Ancol Circuit in Jakarta. Pocholo Ramirez (left) finished a close third, while Indonesian champion Chandra Alim (right) was second.

There was consternation in the Philippine paddock. Tinton was spotted and queried. “No problem. Coming,” he said. “What do you mean, coming? It’s already Friday,” an already exasperated Louie pleaded. Qualifying for the race was on the Saturday. “Here comes qualifying, and still no car. Sunday, race day and still no car. He raced. His car was there,” Louie says. The group was on a flight back from Hong Kong to Manila on Monday, thoroughly dismayed by the situation. “As the plane was taxying, my wife spotted my car being unloaded at the Hong Kong airport! Tinton, he’s a nice guy. I never did race in Macau after that,” revealed Louie.

SILHOUETTE RACING

The Corolla soon made way for something much more competitive once the regulations had loosened up to allow “silhouette” race cars on the grid. These cars had to look like a production car. Out Louie went to analyse the rules and see what he could come up with from his stock of single-seaters. [The history of Silhouette racing in Malaysia can be found in the following article: https://rewind-media.com/2021/08/21/super-saloon-big-bang/ ]

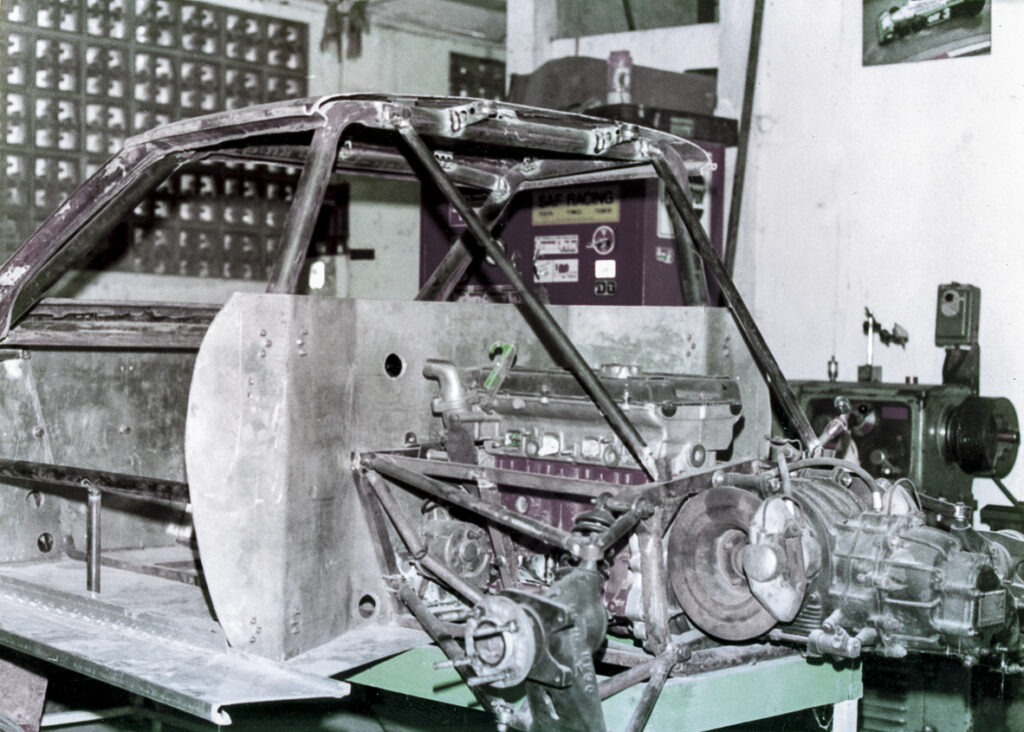

He borrowed fellow racer Narcing de la Merced’s Toyota Celica, and a fibreglass mould of the car was made. De la Merced was going to paint his car, and so agreed to loaning it to Louie as long as it was not destroyed in the mould-making process. The new and very light fibreglass shell was given flared wheel arches. “That Celica of mine felt like a single-seater. Because it was really a single-seater,” Louie declared.

The project was completed in Louie’s shop in Manila with the assistance of his mechanic Bambi Hernandez. “When the guys were getting more competitive,” the Toyota 2TG twin-cam engine was replaced with a hot Cosworth BDA. It was by no means a simple exercise in creating a silhouette race car out of a single-seater. “I transferred the Elfin 620’s suspension to the Celica. I built a new tubular spaceframe for the car. I chopped the Elfin; the front suspension went up front, the rear suspension was grafted on at the back. The BDA engine was put in the rear.”

The project was completed in Louie’s shop in Manila with the assistance of his mechanic Bambi Hernandez.

“I had to move the driver’s seat a little forward to make space for the engine at the back. It took me less than a year to build the car. The body shell was already done two years earlier. My original plan was to make a shell of the Celica with a spaceframe and run it as a Celica, with the engine in front. But when the rules were altered and a new series for Super Saloons was created, it sparked an idea. Pocholo was laughing and told me I was crazy.”

Louie Camus finished third in the Super Saloons race at Shah Alam in September 1983. The Celica still sported its original Toyota 2-litre 2TG engine.

The silhouette Celica was shipped to Shah Alam for the race season. He won his class. “And the beauty about it is that because of the delays in shipment, I did not have a chance to practice,” Louie chuckles. “Unbelievable. I didn’t even tune the suspension, nothing!”

His eyes twinkle as he talks about the Celica. “I’m a mechanical engineer. I love to engineer my racing car. So when I saw the rules, I knew this was it. Without batting an eyelid, I chopped my Elfin.” He continues, “I would put the race car on a trailer at Shah Alam and drive it to Penang behind a rental.” Shah Alam one weekend, Penang the next – it was far less complicated transporting race cars then.

Zul Hassan (left), one of Malaysia’s top saloon racers of the 1980s, shares a laugh with Louie Camus after a race at the Shah Alam Circuit.

MADE IN MANILA

“You know what gave me a feeling of full satisfaction? It was when there were two 935 Porsches that competed in Shah Alam and Penang [the Porsches are featured in https://rewind-media.com/2021/08/21/super-saloon-big-bang/]. The Germans driving those cars were so surprised. On the grid, I was beside the 935 Porsche. Here was a car that cost USD250,000 then. When one of the drivers asked me how much it cost me to build mine, I said about 120,000. ‘Dollars?’ he asked. I said, ‘No, Pesos!’ He was shocked. And here we were, next to each other. The lap times were not too far apart. It was very satisfying,” Louie grins with glee. “Well, let’s face it, racing is expensive. Not everybody could afford it.” His car even made it into a Japanese magazine in an article titled: “Here is a Celica with a BDA engine, and at the back!”

The Penang Grand Prix with works Corolla, Australian-entered Porsche RSR, Schnitzer BMW 320i…and the Celica-Elfin in the background.

On the grid, I was beside the 935 Porsche. Here was a car that cost USD250,000 then. When one of the drivers asked me how much it cost me to build mine, I said about 120,000. `Dollars?’ he asked. I said, `No, Pesos!’

We avoid the sad topic of the subsequent rapid decay of motor sports in the region and what happened to the Celica, but I have it on good intelligence that part of the bodywork of the car still remains in Malaysia. Who knows, one of these days, it may be recovered and returned to the Camus family.

NEED FOR SPEED

Fast forward to 2013, and Louie’s sons are very much involved in the sport. A replica Lola T70 Coupe is parked in the driveway of the family home. One of his sons has prepared it for the Manila Sports Car Club’s race series. “I still do some racing now, in the vintage series in the Philippines. I have a Porsche, a clone RS, a 964 with twin plugs, lightened flywheel, three-plate clutch, upgraded brakes and so forth. It’s a fast car,” Louie tells me as we survey the Lola. “I have to have speed to relax. That’s why free falling and skydiving is the ultimate sport.”

“That parachute malfunction I had was because of some indiscretion on my part. I jumped out of the DC3 and it ripped my chute. Oh my God! You know that things that went on my mind? It can’t happen to me. I was very near the ground when I managed to pull my reserve chute. That’s why I landed on my side.” And that was how Louie Camus ended up motor racing.

One of the earliest races Louie Camus entered with his Celica Super Saloon was in the November 1982 Penang Grand Prix. It was also one of the most exciting Penang races ever, with a works M1 BMW and a brace of Porsches participating.

APPENDIX 1 – THE CELICA ELFIN

By the mid-70s, the spaceframe Elfin 600 and its derivatives were long in the tooth and short on development when compared to the monocoque Brabhams, Marchs and Ralts that were dominating Formula Atlantic/Pacific racing. This in no way stopped those with tighter budgets in Asia from running what was available. Philippine Toyota distributor Dante Silverio met Elfin’s owner Garrie Cooper at Macau in 1971 and purchased two Elfins – a 620 (installed with a Toyota Celica twin cam engine) and a 622 (installed with a smaller Toyota Corolla push-rod engine). The 620s were ideal replacements for the aged 600s and used in Formula Atlantic, Formula 3 and Formula Ford racing and a rumour was circulating around that an order for sixteen 620 Formula Three and Formula Ford chassis had been received by the company for delivery to Asia. This was corroborated with another rumour that a Formula Ford series was being contemplated along with a driving school for the Batu Tiga race trace. Although nothing came of that big order of Elfin 620s, a pair of the 620 series did arrive, consigned to Dante Silverio of the Philippines. The Silverios of course had been dealing with Toyota cars for years and had a ready supply of engines, even if they did not pack enough punch to match the Hart Twin Cams and Cosworth BDAs used by the other international drivers.

Hong Kong racer John Macdonald had a crack in the Elfin 620 Toyota 2TG in the 1973 Marlboro ARAP Open in July and walked away with the win, his first and only go in an Elfin.

In 1972, Toyota works driver Kiyoshi Misaki took the Elfin 620 Toyota twin cam to second place in the Philippines Greenhills Grand Prix while Silverio achieved the same with the 622 Toyota 1.3 in the Automobile Racing Association of the Philippines (ARAP) Open Championships. Persuaded by Silverio, Hong Kong racer John Macdonald had a crack in the Elfin 620 Toyota 2TG in the 1973 ARAP Open in July and walked away with the win, his first and only go in an Elfin. Another Filipino, Butch Viola ran the smaller-engined 622 on a number of occasions, all confined to the Philippines, though with little success.

Forklifting the car in Penang.

Louis Camus ended up buying the Elfin 620 from Silverio. When the Unlimited Formula Super Saloon class of racing in Malaysia was announced, Louie took advantage of the availability of Toyota motors in the Philippines, adapted a Celica body (that’s putting it mildly) with the passenger compartment shifted to accommodate the wider cockpit, and grafted on the Elfin front and rear suspension. It was a silhouette in every sense of the word.

END OF APPENDIX 1

With thanks to the late Louie Camus and his son Bubi and to J.P. Carino for arranging the get-together.